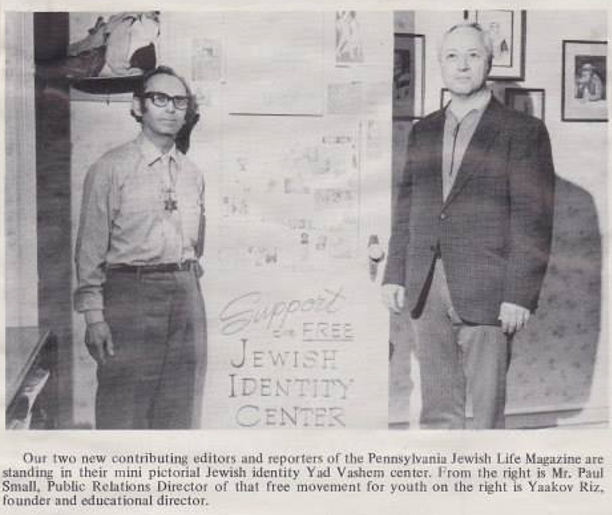

Remembering America's First Holocaust Museum

Neither the Simon Wiesenthal Center’s Museum of

Tolerance in Los Angeles nor the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in the

capital – both opened in 1993 – was America’s first institution dedicated to

the Shoah. That distinction belongs to Yaakov (Jacob) Riz, a Philadelphia Jew

originally from Poland, who maintained a “miniature Jewish Identity Center and

Yad Vashem, the only one in America” [1], in the basement of his home at 1453

Levick Street during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.

“He is about five feet tall and can’t weigh much more

than 100 pounds,” a 1971 Philadelphia Inquirer profile related, also

noting, “He talks incessantly lapsing at times into Russian and translating

into English, singing Yiddish songs, quoting jokes and Jewish stories from

memory and citing newspaper and magazine articles.” [2] More somber than jovial

in the bulk of his public activism, however, Riz purports to have been

“sentenced to death in Soviet Russia as an anti-Communist and Zionist” but

instead “spent several years in a Siberian slave labor camp” [3] – a

Dostoyevskyan origin story bolstering his professed sense of duty to a profound

mission to champion the Jewish people for the remainder of his life.

Born in 1922, “Riz […] was taken to Russia from his

native Poland in 1941,” according to a more detailed biographical summary that

appeared in a 1967 Philadelphia Inquirer article:

As a member of a work

battalion in the Russian army, he was assigned to a factory in Saratov, where

war machinery was being turned out.

Then there was a visit

from the secret police and charges of being a Zionist and a spy for Germany.

For three months he was tortured in an attempt to gain a confession.

“I told them that this

could not be,” he said. “I told them that I was a Jew and I could not be a spy

for the Germans. But then I couldn’t stand it any more. They wouldn’t let me

sleep at night and they beat me and finally I confessed.”

Riz was sentenced to be

shot and placed in a death cell, where each night he could hear the cries of

other condemned men and the shots which ended their anguish. This continued for

42 days, and then he was told that the death sentence had been lifted.

From that point until

1947, Jacob Riz’s life was spent in 10 different slave labor camps in Siberia.

It was especially bad at first.

“They fed us watery soup

and the cabbage was so rotten it had worms in it,” he said. “At first I

couldn’t eat it, but they only laughed at me.”

Then he was taken back to

Poland and freed. A year later, Riz escaped to Israel, where he fought in the

infant nation’s first war for independence and was wounded in the foot. [4]

The Inquirer’s 1985 obituary adds this colorful

anecdote about Riz’s years in Soviet bondage:

He never escaped the

memory of his chilling experience in a camp in Siberia, when he and other

starving inmates butchered and ate the dog of the camp’s commandant. Furious,

the commandant denied the inmates food for three days. [5]

Riz met a Brooklyn woman in Israel, married her, settled

in the United States in 1952, and attended the Jewish Teacher’s Seminary. He

also organized the Yiddish Literature Group of Philadelphia [6], which seems to

have gone by the alternate name of the “Bnai Yiddish Literary Group […] which

fights for Jewish identity” [7]. In addition to establishing his Jewish

Identity Center, Riz served as “principal of the I.L. Peretz Workmen’s Circle

School, whose aim is to preserve the Yiddish language” [8], and positively

pelted newspapers with his letters denouncing communism and anti-Semitism in

his determination to “show the devilish face of the red dictators” [9] and denounce

Nasser as the “Hitler of the Middle East” [10].

“Founder of [the Philadelphia chapter of] B’nai

Yiddish, which he translates Jewish Identity League, Riz is an instructor in

the Workmen’s Circle schools, cultural director of Circle Lodge, the Arbeiter

Ring summer camp in Hopewell Junction, New York and an indefatigable writer of

letters to the editor,” noted Rabbi Samuel Silver in The Indiana Jewish Post

and Opinion in 1970, also lauding him as a “zealot […] on behalf of Yiddish”

[11]. In the activist field, Riz made a name for himself when he picketed a

performance of the Moscow Circus in Philadelphia in 1967 [12] and later protested

a public school textbook that “contained ‘seeds of animosity towards Jews’”

[13].

Given his militancy, paranoia, and ardent anti-Soviet

orientation, it is interesting to observe that Riz’s Jewish Identity Center in

Philadelphia bore the same name as the Jewish Identity Centers established by

the followers of Meir Kahane, founder of the terrorist Jewish Defense League, in

New York, Jerusalem, and Montclair, New Jersey. The leftist Jewish Currents

reported that on December 2, 1970, “the Executive Board of B’nai Yiddish in New

York expelled Jacob Riz of its Philadelphia chapter for using B’nai Yiddish to

promote the JDL politics” [14]. Just a few days earlier, as The New York

Times reported:

A pipe bomb exploded in

the doorway of the Soviet Union’s airline and tourist agency offices at 45 East

49th Street […] shattering windows in the two‐story structure and causing

slight damage to displays.

[…] transmissions from

radio station WMCA, which has offices nearby, were interrupted for about 15

minutes because of a damaged underground cable.

About 25 windows in an adjacent

building were also damaged, and two windows and the metal skin of a building

across the street were punctured by flying debris. […]

A short while after the

bombing, anonymous telephone callers told The Associated Press and United Press

International that the bombing was to protest what they described as the

forthcoming trial of Soviet Jews accused of trying to hijack an airliner last

June. […]

The four identical calls

ended with the phrase “never again.” This phrase has been used as a rallying

cry by the Jewish Defense League, a militant organization that has been

picketing offices of the Soviet Union here to protest the condition of Jews in

Russia.

Rabbi Meir Kahane,

national director of the organization, denied yesterday that any member of his

group had been involved in the incident, but he said that he “heartily applauded”

the action. [15]

Remembrance of the Holocaust and the plight of Jews in Israel and in the Soviet Union remained at the fore of Riz’s concerns. In the Spring 1973 issue of Aleichem Sholem, “Official Publication of the Student Committee for Yiddish”, Riz published an urgent item in which he expressed alarm that “even our own people are forgetting” the Holocaust and called for “the establishment in every city of free Jewish identity information centers where a small Yad Vashem [i.e., a Holocaust memorial] would be included.” “Such a center would be open daily and would include a shtetl room, a holocaust room, an Israel past room, an Israel present room, an American Jewry room and a diaspora room,” he further detailed [16].

In Torn at the Roots: The Crisis of Jewish

Liberalism in Postwar America, Michael Staub writes that, “when Breira, an American

Jewish center-left coalition group comprised of rabbis and Jewish intellectuals

and writers, counseled in the mid-seventies that American Jews should work

toward a peaceful solution of the Middle East crisis and urged that Israel help

establish a sovereign Palestinian state, the countercharges from right-wing

American Zionists did not hesitate to bring in the Holocaust,” giving the

example that “rabbis affiliated with Breira should be fired, Yaakov Riz of the Jewish

Identity Center in Philadelphia wrote in 1974, because they were ‘acting as the

“Yudenrat” in the Nazi concentration camps where my family perished.’” [17]

According to Riz’s 1985 obituary in The

Philadelphia Inquirer, “He had believed himself the only member of his

family to survive through World War II until 1960, when his brother Moishe

found him.” [18] In the summer of 1973, Riz traveled to Israel, where he was

reunited with Moishe, as he would reveal in the pages of Pennsylvania Jewish

Life [19]. This contradicts other accounts, such as a 1970 Philadelphia

Inquirer article claiming that Riz’s “family was wiped out by the Nazis in

Poland” [20] and a 1983 Miami Herald profile that asserts Riz’s “whole

immediate family and 83 of his relatives had been exterminated at Auschwitz” [21].

One is tempted to wonder, too, what documentation actually exists for the story

that those other eighty-three people were “exterminated at Auschwitz”.

Another recurring theme of Riz’s many letters is his need of more money to keep the Jewish Identity Center in his basement operational. Persistently radical, Riz in 1977 wrote a letter to The Indiana Jewish Post and Opinion in which he discussed “the answer on how to combat the [Christian] missionaries, the evil ‘religious’ cults, by establishing free places for lost Jewish youth.” Citing the Talmud and indicating that he could better combat the missionaries with generous funding, he further implored:

Let us start spending our

Jewish money for real Jewish causes! For our own Jewish survival. Because after

Auschwitz everything is possible. I know it. I’m a survivor off [sic] the

Holocaust. [22]

In 1980, when the Institute for Historical Review

offered $50,000 to anyone who could produce proof that Jews had been gassed at

Auschwitz, Riz announced that he and Petro Mirchuk, a leader of the Banderist Organization

of Ukrainian Nationalists who had been interned at the camp, “have attorneys

who are looking into this case to sue them for a million dollars.” “What can

survivors do?” Riz further posed:

First of all write […]

asking to claim the $50,000 dollars.

2) Send to me all the

information if you witnessed the gassing of the Jews in the different death

camps, and I will give the material over to my attorneys who are working on the

case. [23]

Ironically, though Mirchuk capitalized on his internment at Auschwitz to establish his own moral authority as a Holocaust survivor, Riz’s fellow schemer in proposed litigation seems to have been anti-Semitic, himself. “What is ‘Jewish justice’ doing in American courts?” Mirchuk mused in another context: “And why ‘Jewish’ and not American justice? Are we a colony of theirs? It’s not enough that our government gives Israel billions of our tax money each year for nothing, and now American courts must yield to Jewish demands?” [24] In the end, it was Mel Mermelstein who won fame as the slayer of “Holocaust denial” when a court took “judicial notice” of the “fact” that Jews had been gassed at Auschwitz and ordered the IHR to pay him $90,000 [25].

Riz did, however, earn himself a mention in the Summer

1980 issue of The Journal of Historical Review:

A Mr. Yaakov Riz of 1453

Levick Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, operates his own “Holocaust” Museum

out of his basement, under the auspices of what he calls the “Brotherhood to

Prevent Genocide”. He displays a jeweled soap dish inscribed “Soap Made of

Jewish Bodies” complete with a fragment of soap which is claimed to be made of

human fat. However, no forensic analysis has ever been made of the soap. [26]

Riz’s name appeared again in The Journal of

Historical Review the following year:

Mr. Riz wrote to the Jewish

Press on 5 September 1980 to point out how “the Talmud teaches us how to

use Visual Propaganda.” He quotes a passage from the Talmud where the Angels

Gabriel and Michael tricked God into drowning the wicked Egyptians by showing

him an Egyptian brick and a dead Jewish child. Riz vigorously advocates using

the same trickery to combat the wicked “Arabs, Nazis and Communists” who

otherwise are “winning their filthy hate campaign against Israel and American

Jewry.” One wonders what Talmudic trickery Riz and his cohorts have used

already? [27]

In a way, Riz was ahead of his time in his conviction that museums dedicated to the memory of the Holocaust could be extremely useful in indoctrinating both Jews and non-Jews in the demonization of critics of Zionism. Alas, the diminutive, goblin-like Riz with his ramshackle basement collection of horrors and propaganda literature, was not the man to bring this potential to full fruition. Following his death, Riz’s collection was relocated to accommodations at Gratz College in Melrose Park and dubbed the “Holocaust Awareness Museum”. In 1998 it was merged into a similar exhibit in Cherry Hill, New Jersey [28], then moved to the KleinLife community resource center in Philadelphia, and today Riz’s collection is recognized as the progenitor of the Holocaust Awareness Museum and Education Center based in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania [29]. “The museum has educated hundreds of thousands of students and adults in schools, community groups, and organizations since its inception,” reads the organization’s website: “During the 2019-2020 school year, our educational programs reached 23,750 students and adults in 175 schools, organizations, and businesses. Our programs emphasize the message that racial, ethnic, and religious hatred are social poisons that weaken American democracy.” [30] HAMEC’s website makes no mention of Jew-lard soap, but one hopes that Riz’s specimen is still being preserved somewhere as evidence of the waking nightmares that European notions of racial hygiene have produced.

Rainer Chlodwig von K.

Rainer is the author of Drugs, Jungles, and Jingoism.

Endnotes

[1] Riz, Yaakov. “The Need for Jewish Identity

Centers”. Aleichem Sholem (Spring 1973), p. 10.

[2] Wallace, Andrew. “Jewish Identity Center Is Goal

of Refugee from Oppression”. The Philadelphia Inquirer (November 27,

1971), p. 4.

[3] “Ohev Speaker Sets Talk on Communism”. Delaware

County Daily Times (December 8, 1965), p. 19.

[4] Lloyd, Jack. “Moscow Circus Show Spurs Clashing

Plans for Protest, Praise”. The Philadelphia Inquirer (November 6,

1967), p. 25.

[5] Heidorn, Rich. “Yaakov Riz, 63, Retired Educator”.

The Philadelphia Inquirer (December 21, 1985), p. 5-B.

[6] “Ohev Speaker Sets Talk on Communism”. Delaware

County Daily Times (December 8, 1965), p. 19.

[7] “Historical Editorials”. The Philadelphia

Inquirer (January 11, 1969), p. 6.

[8] “Letters to the Editor”. Philadelphia Daily

News (March 19, 1963), p. 33.

[9] “Letters to the Editor”. Philadelphia Daily

News (June 3, 1967), p. 15.

[10] “Middle East Munich”. The Philadelphia

Inquirer (October 6, 1968), Section 7, p. 4.

[11] Silver, Samuel. “Keep the Yid in Yiddish”. The

Indiana Jewish Post and Opinion (July 17, 1970), p. 11.

[12] Lloyd, Jack. “Moscow Circus Show Spurs Clashing

Plans for Protest, Praise”. The Philadelphia Inquirer (November 6,

1967), p. 25.

[13] Silver, Samuel. “Keep the Yid in Yiddish”. The

Indiana Jewish Post and Opinion (July 17, 1970), p. 11.

[14] Schappes, Morris U. “Around the World”. Jewish

Currents (January 1971), p. 54.

[15] Narvaez, Alfonso A. “Bomb Damages Russian Offices

Here”. The New York Times (November 26, 1970): https://www.nytimes.com/1970/11/26/archives/bomb-damages-russian-offices-here-soviet-jews-plight-cited-by.html

[16] Riz, Yaakov. “The Need for Jewish Identity

Centers”. Aleichem Sholem (Spring 1973), p. 9.

[17] Staub, Michael E. Torn at the Roots: The

Crisis of Jewish Liberalism in Postwar America. New York, NY: Columbia

University Press, 2002, p. 17.

[18] Heidorn, Rich. “Yaakov Riz, 63, Retired

Educator”. The Philadelphia Inquirer (December 21, 1985), p. 5-B.

[19] Riz, Yaakov. “My Visit to Israel”. Pennsylvania

Jewish Life (October 1973), p. [?].

[20] “Jewish Group Still Battles Yippie’s Book”. The

Philadelphia Inquirer (November 29, 1970), p. 11.

[21] Wolf, Kenneth L. “Holocaust Lives for Freedom

Fighter”. The Miami Herald (July 16, 1983), p. 5PB.

[22] Riz, Yaakov. “Free Places Where Lost Youth Can

Meet to Combat Christian Missions”. The Indiana Jewish Post and Opinion

(August 19, 1977), p. 14.

[23] Riz, Yaakov. “Group Challenging Holocaust to Be

Sued”. The Indiana Jewish Post and Opinion (February 15, 1980), p. 21.

[24] Rudling, Per A. The OUN, the UPA and the

Holocaust: A Study in the Manufacturing of Historical Myths. Pittsburgh,

PA: Center for Russian and East European Studies, 2011, p. 59.

[25] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mel_Mermelstein#The_Institute_for_Historical_Review

[26] Harwood, Richard; and Ditlieb Felderer. “Human

Soap”. The Journal of Historical Review (Summer 1980): https://ihr.org/jhr/v01/v01p131_Harwood.html

[27] Brandon, Lewis. “The Big Lie Technique in the

Sandbox”. The Journal of Historical Review (Spring 1981): https://www.ihr.org/jhr/v02/v02p-35_Brandon.html

[28] Charlton, Faith. “Teaching Tolerance through the

Lens of the Holocaust: The Goodwin Holocaust Museum and Education Center of

South Jersey”. Concept (April 2006), pp. 95-96.

[30] Ibid.

Comments

Post a Comment