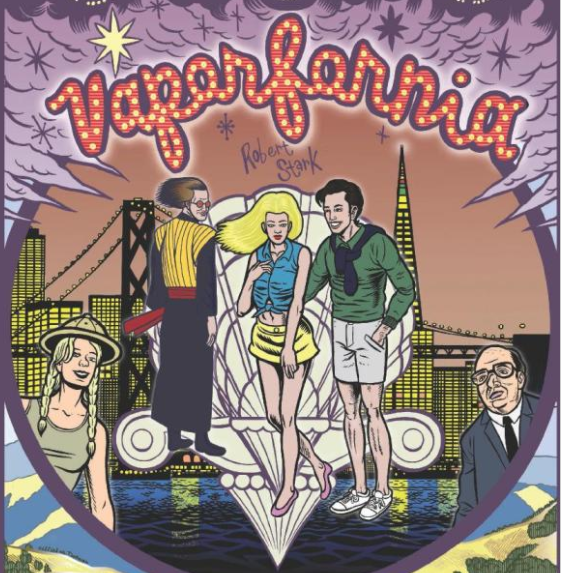

Una Película Bioleninista

Neoreactionary Bloody Shovel blogger Spandrell

has written extensively on the topic of Bioleninism, the twenty-first century’s

answer to now-quaint Marxism-Leninism [1]. As Clown World Chronicles

author Vince McLeod summarizes the phenomenon, it consists of “social rejects

coming together to force their will on society at large” [2], with the

aspiration to a dictatorship of dysfunctional, defective, and low-status people

taking the place within Bioleninism that the dictatorship of the proletariat

takes in Communism. Further accounting for the rise of such societal currents

is Edward Dutton’s discussion of the proliferation of “spiteful mutants” as a

result of weakened natural-selection pressures in the modern world [3]. Decades

before Bioleninism had a name, however, this dysgenic strain of revolutionism received

striking cinematic representation in the 1993 Spanish film Acciόn Mutante.

Co-written and directed by Álex de la Iglesia, “an

important nutter in the history of Spanish cinema” in the words of actor

Antonio Resines [4], Acciόn Mutante follows the futuristic exploits of

the titular gang of malformed terrorists, led by the facially disfigured thug-mastermind

Ramόn Yarritu (Resines). The film opens as members of the group are binding and

gagging a bodybuilder in a botched kidnapping attempt, having already murdered

his lover – all part of the gang’s guerrilla campaign against various

manifestations of the ideal, with “goodlooking celebrities and institutions

related to public health and sperm banks” as symbols of eugenics having “been

their specific targets” and previous actions having included the failed kidnapping

of a plastic surgeon and the bungled bombing of a fashion show. “We’ll kill

beauties with or without you,” as the Acciόn Mutante rap-rock theme song

by Def Con Dos puts it.

Militants include Siamese twins Álex and Juan Abadie (Álex

Angulo and Juan Viadas), the deaf and dumb oaf M.A. (Alfonso Martínez), “who

has one of the lowest IQs on the planet”, and José Tellería, alias “Handyman”

(Karra Elejalde), the gang’s mechanic. Conceding the alignment of the ragtag coalition

of the fringes with Jewish interests but stopping short of attributing a Bioleninist

leadership role to the Jews, the assortment of maladaptive terrorists also includes

César Ravenstein (Saturnino García), who keeps a load of dynamite permanently

strapped to his chest, and José Montero, a hunchbacked dwarf, “Jew, Mason,

communist and presumed homosexual.” Collectively, the band of antiheroes stands

for the ascendancy of the “Freak Power” advertised by solidaristic graffiti.

|

| The Abadie twins confer with Handyman after a gooey eruption. |

The main plotline concerns the scheme of Ramόn Yarritu to kidnap a beautiful, blonde, just-married bread heiress, Patricia Orujo (Frederique Feder), and spirit her off to the planet Axturias, where her fascistic father, El Ominoso Orujo (Fernando Guillén), is expected to pay a sizeable ransom. “We’re soldiers in the mutant army and we’re going to win the war,” Ramόn explains to his henchmen in a motivational speech:

Society has treated us

like shit and now we’re going to kick some ass! The world is dominated by

pretty boys and spoiled brats. God! Enough of this “diet” shit! We’ve had

enough colognes, car commercials, mineral water! We don’t want to smell good!

We don’t want to lose weight! We’re the only ones left, my friends. The rest of

the world are either stupid or hipsters. We are mutants, not beach boys or

design faggots! And now, let’s show those shits what terrorism means.

As Álex Abadie discovers, however, his leader’s

revolutionism is insincere, Ramόn’s actual intention being to betray his fellow

rebels and keep the entire ransom for himself. “What was I when my mother had

me?” he muses, finally revealing his egoistic motivation: “Number one, the

best! And who made me what I am? Me, without anybody’s help. And what am I? The

fucking boss!” It is, however, Álex – who, significantly, shares his first name

with writer-director Álex de la Iglesia – who in the end will be rewarded by

his loyalty to the anti-ideal of the dysgenic rebellion.

|

| Ramόn and Patricia arrive at their rendezvous point on the planet Axturias. |

Acknowledging the influence of Delicatessen (1991) and Freaks (1932), Álex de la Iglesia has said that “Acciόn Mutante is a sort of explosion of wanting to tell a thousand things and to laugh at a thousand things from a cynical perspective.” A natural contrarian, he professes to be “morally against everything. And that’s where I find humor and the main purpose for making films. It’s a sort of revenge on imposed things. […] If everyone says this is good, I’ll find it bad. […] I feel like being in opposition to the public opinion, which is built by the media and doesn’t match at all what I want to say and feel in life.”

The Basque background of both Álex de la Iglesia and

co-writer Jorge Guerricaechevarría also infuses the film with its

confrontational outsider perspective. “Violence, terrorism, and that sort of brutal

and harsh public opinion, telling you what to think and what to focus on, fried

our brains,” the director insists. A sequence in which the terrorists’ vessel

is monitored and its crew interrogated by authorities “talks a lot about the

reality that prevailed in the Basque country,” according to Guerricaechevarría:

Police control was

something that could occur during any weekend on any road and it was rather

sinister and quite disturbing. Suddenly coming across a control point. “Stop

here.” […] Those were situations that we faced naturally, yet without losing

that degree of tension and hidden violence. […] We were doing a parody of

something that affected us, it was conditioning people’s lives. We kind of took

it out of the political context and took it to a more universal terrain or a terrain

where it could work better for us: the struggle between the ugly and the

pretty, between that perfect world which they try to sell us day after day, and

ugly people […]

As such, Acciόn Mutante constitutes a cinematic

Antifa classic – a gory, insanely violent, slime-spewing spite-fest with a grimy

sub-cyberpunk aesthetic and futuristic vision reminiscent of Total Recall

(1990) – and fully justifies Resines’s praise of its auteur as “an

important nutter in the history of Spanish cinema” and, it should be added, an

artistic terrorist of note in the history of genre filmmaking more generally.

Rainer Chlodwig von K.

Rainer is the author of Drugs, Jungles, and Jingoism.

Endnotes

[1] Spandrell. “Biological Leninism” (2017): https://archive.org/details/spandrell-biological-lenninism/mode/2up

[2] McLeod, Vince. “Clown World Chronicles: What Is ‘Bioleninism’?”.

VJM Publishing (August 1, 2020): https://vjmpublishing.nz/?p=21454

[3] Dutton, Edward. “How Can You Tell That Someone’s a

Spiteful Mutant?”. The Jolly Heretic (March 29, 2023): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HQVNJZWpv2c

[4] All quotations are drawn from interviews included

on the 2023 Severin Films Blu-ray release.

Comments

Post a Comment