Temple Macbeth Israel: Shakespeare, Polanski, Capote, and the Kennedy Assassinations

Two weeks ago, in “The Merrick Connection Revisited”, I

discussed the fascinating interconnectivity of the Tate-LaBianca and Kennedy

assassination nexuses – and readers are advised to acquaint themselves with the

arguments I present in that essay before proceeding. Last week, I analyzed the

Manson-Kennedy-resonant subtext of Roman Polanski’s 1988 thriller Frantic,

and now I intend a similar approach to 1971’s Macbeth, the first film

Polanski completed following the Tate-LaBianca massacres. “Polanski's first

celluloid hero after that grizzly [i.e., grisly] night is a man who is

delivered into the world via a bloody cesarean section performed with a sharp

knife,” notes G. Greene-Whyte, writing at The Manson Family Blog, also

observing that, “The director flashes a baby being removed from his mother’s

womb across the screen twice during the film.” “I feel like Polanski punished

himself with this project,” Greene-Whyte concludes:

The self-harm never stops. Polanski

assaults himself with this work. Our hero Macduff is asked by future king

Malcolm why he (Macduff) fled to England and left his defenseless wife,

children, servants, and castle household behind so they were easy victims for

Macbeth’s evil men. [1]

The sense of relevance to recent events is reinforced by the

Third Ear Band’s psychedelic soundtrack contributions and the abundance of men

with long hair and beards, whose wardrobe and communal sleeping arrangements

might not be out-of-place at some occult happening of the sixties. “It’s as if

the play has been inhabited by Hell’s Angels who are quick studies,” remarks

Roger Ebert in his review. There is, as well, the mention of a “shard-borne beetle”

– or is it the Beatles, with “Helter Skelter”? – whose “drowsy hums” conclude a

night on which is committed a “deed of dreadful note.” “I might as well be

honest and say it is impossible to watch certain scenes without thinking of the

Charles Manson case,” Ebert continues: “It is impossible to watch a film

directed by Roman Polanski and not react on more than one level to such images

as a baby being ‘untimely ripped from his mother’s womb.’”

Greene-Whyte has suggested Macduff as “Polanski’s […] hero”. He is not, however, Polanski’s protagonist, as Ebert recognizes: “in this film Polanski and his collaborator, Kenneth Tynan, place themselves at Macbeth’s side and choose to share his point of view,” he contends. There is arguably some ambiguity as to whether Polanski corresponds to Macbeth or Macduff. “Why did Polanski choose to make Macbeth,” Ebert wonders without offering an answer, “and why this Macbeth?” [2] The reason Polanski selected Macbeth is that its story is not strictly personal, but political and conspiratorial – and therefore an unexpectedly appropriate production for Hugh Hefner’s CIA front Playboy. Shakespeare’s tragedy is also concerned with espionage, with Macbeth consulting the “strange intelligence” of the three witches. Moreover: “There’s not a one of them but in his house / I keep a servant fee’d,” Macbeth reveals - or, as the movie’s screenplay words it, “There’s not a one of them but in his house / I keep a servant paid.”

Shakespeare’s Macbeth, with its murderer’s hope that “the assassination / Could trammel up the consequence”, had enjoyed an explicit association with the plot against John F. Kennedy since the 1966 publication of Barbara Garson’s satire MacBird! in Ramparts. The Kennedy presidency’s Arthurian Camelot mythos finds a complement in Shakespeare’s drama of a medieval regicide, which Garson appropriates as a humorous spin on Lyndon Johnson’s ascendancy. “The play is often seen as an indictment of Johnson and his possible role in the Kennedy assassination,” writes Tom Dalzell. However, “Garson disputes this,” he continues, quoting her not-very-convincing rationale years after the fact: “This play wasn’t anti-LBJ, and it didn’t seriously suggest that he had President Kennedy killed. What I saw was that the Kennedy family and Johnson had the same politics, yet the Kennedy men were considered so beautiful and Johnson was considered so ugly. Why was that?” Garson, quirkily enough, had been a supporter of the infamous Fair Play for Cuba Committee, of which Lee Harvey Oswald would join the New Orleans chapter [3]. Her husband, Marvin Garson, edited the San Francisco Express Times, and is noteworthy for opining that “the Sixties were entirely staged”:

I do not mean that certain events

in the Sixties were staged (civil rights movement, Cuban missile crisis,

Vietnam war, demonstrations, riots and assassinations); of course they were and

everybody knows it. Nor do I mean that certain people and groups did some of

the staging (CIA, SDS, Mafia, television networks, various politicians); again,

everybody knows and nobody cares.

No, when I speak of “The Staged

Sixties” I mean a decade entirely staged down to the tiniest “accidental” details

of timing, costume, names of characters, etc. I am referring to the kind of

really big scale production which it was once thought could only be mounted by

the invisible God of the Jews.

“Act II” of the decade, Mr. Garson says, consists of a

“tragic assassination, tragic riots, tragic war,” while “Act III (beginning in

1968)” opens with the “supreme anguish […] the assassination of Bobby Kennedy”

but closes with “a surprise happy ending.” [4] There is a fair chance that

Polanski was familiar with Garson’s wife’s play MacBird!, as it was

staged in London during the period when the director lived there [5], so it is

possible that it influenced Polanski’s decision to bring a contemporarily

political version of Shakespeare’s original to the screen. Professor Stephen M.

Buhler notes a commonality in the messaging between Garson’s play and

Polanski’s film. “Garson has already suggested that the regime which will

replace that of her Macbeth figure is not substantially different from the

tyrant’s own,” Buhler writes. “Such an interpretation of Shakespeare’s text

would be realized for the screen by Roman Polanski,” he then suggests [6].

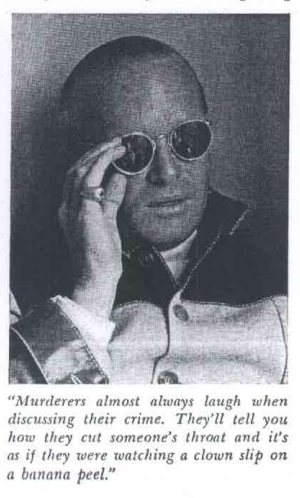

|

| Polanski on the set of Macbeth |

Has the auteur, as Greene-Whyte indicates, “punished himself” by making Macbeth? Possibly – but an anecdote from Christopher Sandford’s biography Polanski suggests that the atmosphere on the set was less than consistently solemn, let alone anguished: “The director took time away from the concluding scenes to assemble a group of elderly female extras,” he relates, “and film them in the nude singing ‘Happy Birthday, Hef’.” [7] He also reportedly referred to performers as “monkeys” [8]. Polanski is probably having a black chuckle in casting an actor named Balfour in the role of the First Murderer – the Balfour Declaration of 1917 having formalized Britain’s tentative assent to Zionist claims to Palestine, and the Manson-and-Sirhan-connected Process Church, readers may remember, had established itself at 2 Balfour Place in London in 1966 [9] – an esoteric acknowledgment of Israel’s hand in the murders of JFK and RFK. Perhaps relevant to Polanski’s theme, Shakespeare informs the reader that the first scene of his play transpires in a “desert place”. Macbeth, like the arrogant Zionists, is moved by evil prophecy to commit his political crimes and atrocities. Polanski, too, had originally wanted Richard Burton to appear in Macbeth [10], which would have amplified the story’s Kennedy association, as Burton had been the star of the Broadway production of the Lerner and Loewe musical Camelot, a favorite of President Kennedy [11].

As “blood will have blood”, King Duncan’s assassination precipitates

a series of other murders – most notably, that of Banquo, who himself threatens,

as the witches have foretold, to become “father to a line of kings”. Robert F.

Kennedy, in contesting the presidency in 1968, presented the similar danger of

perpetuating a hated political dynasty, and – like the noble Banquo in Polanski’s

Macbeth – he was assailed from behind. Whether by design or not, the

recurrence in Macbeth of the word “thane” calls to mind Thane Cesar, the

security guard believed by many researchers to have fired the shots that killed

Senator Kennedy [12]. It may also be worth mentioning that Playboy, the

organ of Macbeth producer Hugh Hefner, had not exhibited a consistently

friendly attitude toward Kennedy. “RFK’s critics warn that his past actions –

including his work for Joe McCarthy and his hounding of Jimmy Hoffa – would make

him a dangerously authoritarian President likely to run roughshod over the

civil liberties of his opponents,” Playboy interviewer Eric Norden had

posed to Truman Capote in 1968 [13]. Another of the deaths resulting from

Duncan’s murder is that of Lady Macbeth herself. Though Greene-Whyte finds in

Macduff’s wife the obvious figure corresponding to Sharon Tate, it is after

Lady Macbeth’s demise that the tragic protagonist offers his soliloquy on the “poor

player”. That Lady Macbeth’s downfall is self-inflicted calls into question

Polanski’s own understanding of the reasons for his wife’s death.

|

| The First Murderer (Michael Balfour, center) watches as Banquo (Martin Shaw) dies |

Truman Capote, in cryptic fashion, would reinforce the Kennedy-Macbeth connection with a strange piece of writing titled “Then It All Came Down”, one of the “conversational portraits” included in his 1980 book Music for Chameleons. The title alludes to the scene of Banquo’s murder in Shakespeare’s play, when the First Murderer, in reply to his victim’s remark, “It will be rain to-night”, answers, “Let it come down.” Purporting to record a conversation Capote had with Bobby Beausoleil in San Quentin sometime during the early seventies, “Then It All Came Down” is a teasing, insinuating mix of accusation and confession, sometimes verging on homosexual erotica. George Stimson, in his post “Truman Capote’s Credibility”, persuasively casts doubt upon the reliability of the writer’s “nonfiction” body of work and particularly the “transcript” of Capote’s conversation with Beausoleil, noting that the latter, at a 2005 parole hearing, even went as far as to claim, “Apparently it was something that he [i.e., Capote] took out of his own head.” [14]

The “conversational portrait” is nevertheless revealing in

its juxtaposition of the Kennedy assassinations and the Tate-LaBianca murders in

Capote’s deceptively casual chat. “Had a little talk with Sirhan,” Capote has

himself volunteering before broaching the subject of the Manson Family,

expressing an interest in the alleged assassin’s emotional state. “I was

thinking,” Capote muses: “I know Sirhan, and I knew Robert Kennedy. I knew Lee

Harvey Oswald, and I knew Jack Kennedy. The odds against that,” he sarcastically

marvels – “one person knowing all four of those men – must be astounding.” [15]

Indeed, it strains the perennial argument for coincidence, prompting the

question of whether Capote was just a celebrity litterateur or something

else – and, if so, what his motives were in visiting Beausoleil and Sirhan

in San Quentin. Was he only seeking material for his writing, or was he in

effect conducting unofficial interrogations? Was he, perhaps, motivated to

probe Beausoleil to discover how much he knew about the RFK assassination?

“The CIA has a file on him consisting of one document, and

that was denied me,” relates Herbert Mitgang, who researched the subject of government

surveillance of authors for a 1987 New Yorker article. “The FBI said

that Capote had ‘never been the subject of an FBI investigation’,” he

continues:

However, he was identified in

numerous files relating to other individuals and to various organizations. […]

Since so many pages in his file

were withheld, I don’t know whether Capote was indeed listed as a security

risk.

Explaining the reason for some of

the censored material, the FBI said in a letter to me, “Information has been

deleted which originated with the United States Senate Subcommittee to

Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and other Internal

Security Laws of the Committee on the Judiciary, Fair Play for Cuba Committee,

January 6, 1961, in Executive Session. […]”

The final entry in Capote’s file is

dated May 23, 1968, and originated in Los Angeles. It reveals that an informant

was tracking someone who was known to Capote. This somewhat mysterious entry

goes, “He was advised by Capote that [name censored] is staying in some

friend’s home in Palm Springs while he is rewriting some portions of his book

[title censored]. Capote could not recall the name of the street but said it

was some ‘Circle’ approximately one mile from downtown Palm Springs.” [16]

Mitgang neglects, at least explicitly, to consider the possibility that Capote, rather than being a victim of the security state, instead could have been one of its intelligence assets. It is an intriguing question to ponder given Capote’s multiple visits to the Soviet Union during the Eisenhower years. “Truman Capote’s epic trip to the USSR inspired the future author of Breakfast at Tiffany’s to write a biting account of his experiences during the days of the Cold War,” summarizes Valeria Paikova [17]. What she fails to mention about his “incredible adventure” is that the production of Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess with which Capote traveled to Leningrad and Moscow was sponsored by the US Department of State. Before embarking, the cast, crew, and embedded journalists were assembled “for a ‘briefing’ to be conducted by Mr. Walter N. Walmsley, Jr., and Mr. Roye L. Lowry, respectively Counsel and Second Secretary of the American Embassy in Moscow.” [18] “A member of the cast […] raised his hand to ask a question,” Capote recalls: “He wanted to know, ‘Suppose some of these [Russian] people invite us into their home? See, most places we go, people do that.” The answer indicates the potential intelligence-gathering utility of the traveling company:

The two diplomats exchanged an

amused glance. “As you may well imagine,” said Mr. Walmsley, “we at the Embassy

have never been bothered with that problem. We’re never invited anywhere.

Except officially. I can’t say you won’t be. And if so, by all means

take advantage of the opportunity. [19]

“Half fascinated, half terrified, Capote returned to Moscow

twice in the 1950s,” Paikova continues:

There, he met a bunch of youngsters

born with a silver spoon in their mouth, mainly the sons of artists, scientists

and diplomats. This encounter had a strong impact on Capote. In the late 1950s,

he started writing another report for The New Yorker. It focused on the

gilded youth, whom Capote broadly described as the “sons and daughters of the

Russian revolution”. To gather material and meet people and put flesh on

the bones of his story, Capote returned to the USSR two more times, in 1958 and

1959. [20]

It was on the 1959 jaunt, Capote

has himself telling Beausoleil in “Then It All Came Down”, that he had his

encounter with “paranoid hysteric” Lee Harvey Oswald:

I met him just

after he defected. One night I was having dinner with a friend, an Italian

newspaper correspondent, and when he came by to pick me up he asked me if I’d

mind going with him first to talk to a young American defector, one Lee Harvey

Oswald. Oswald was staying at the Metropole, an old Czarist hotel just off

Kremlin Square. […] And there he was, sitting in the dark under a dead palm

tree. Thin and pale, thin-lipped, starved-looking. […] And right away he was

angry – he was grinding his teeth, and his eyes were jumping every which way. [21]

1966, the year of In Cold Blood’s

publication, also witnessed Capote’s Black and White Ball at the Plaza Hotel in

New York City. “Truman’s guest list was a glittering assortment of men and

women, top heavy with figures prominent in finance, medicine, politics,

publishing, and society as well as the fine and applied arts,” explains Sarah

Rodman:

Quite a few of Truman’s invitees

were openly, or covertly, cooperating with initiatives linked to the United

States’ government-directed Cold War intelligence and security efforts then

underway to influence domestic and global public opinion, promote democracy,

and defeat Communist-led regimes around the world. The party was, possibly, the

largest gathering of “witting” and “well-heeled” spooks ever assembled.

Months later, these secret

initiatives were revealed and began to unravel when Ramparts magazine’s

March 1967 edition included a story lifting the veil on the Central

Intelligence Agency’s funding of American and international organizations as

well as journalists, a number of whom had been invited to Truman’s party. [22]

Capote, like Vincent Bugliosi, his fellow bestselling “true crime” luminary, would wield his celebrity in defense of the establishment narrative on the John F. Kennedy assassination. “The Warren Report is correct,” Capote asserts in a March 1968 Playboy interview. “Oswald, acting alone, killed the President. And that’s it,” he insists, proceeding to thrash Orleans Parish District Attorney Jim Garrison:

I’m unable to

understand why any intelligent and objective person cannot clearly see the

basic correctness of the Warren Report. But I do understand very well

all this nit-picking and speculation that’s going on, because most of it is

monetary: a bunch of vultures has discovered that pecking at the carrion of a

dead President is an easy way to make a living. […]

Mr. Garrison is on

to something, all right – a good press agent. As far as I’m concerned, Garrison

is a man on the make politically who’s seized hold of this alleged conspiracy

as a method of advancing his career. But I think he bit off more than he can

chew and is now forced to ride the thing to the dirty end. I’ll bet Garrison is

sorry he ever started his so-called investigation. […]

If Garrison really

does have anything at all to back up his charges, it will be a great surprise

to me. I think he’s a faker. […]

Of course I’m

prejudging the case, for the simple reason that I don’t believe he has

any case. The man has behaved with outrageous irresponsibility, caused great

emotional damage to a number of innocent people and, in general, conducted

himself in a manner that makes Huey Long look like Orphan Annie. I’m not going

to suspend my critical faculties just because the jury hasn’t rendered a

verdict. And if the jury did find Shaw guilty, I would still refuse to

believe Garrison has a case. [23]

More than a decade later, Capote still feels the need to

discredit the Garrison investigation. In “Hidden Gardens”, another of the

“conversational portraits” included in Music for Chameleons, Capote

continues to champion Clay Shaw, his fellow New Orleans homosexual, describing

him as “a gentle, cultivated architect who was responsible for much of the

finer-grade historical restoration in New Orleans. At one time,” he snipes,

“Shaw was accused by James Garrison, the city’s abrasive, publicity-deranged

DA, of being the key figure in a purported plot to assassinate President

Kennedy. Shaw stood trial twice on this contrived charge, and though fully

acquitted both times, he was left more or less bankrupt,” Capote weeps: “His

health failed, and he died several years ago.” In “Hidden Gardens” the author

even acknowledges knowing and corresponding with Shaw: “After his last trial,

Clay wrote me and said: ‘I’ve always thought I was a little paranoid, but

having survived this, I know I never was, and know now I never will be.’” [24] To

Capote’s peculiarly interconnected set of acquaintances including JFK, RFK, Jay

Sebring, Sharon Tate, Abigail Folger, Voytek Frykowski [25], Lee Harvey Oswald,

and Sirhan Sirhan, therefore, must be added the shadowy Clay Shaw.

Stimson, in critiquing Capote’s account of his meeting with Beausoleil, complains, “Capote has the name of the second half of the collective murders attributed to the ‘Manson Family’ as ‘Lo Bianco’ not ‘LaBianca’.” [26] One wonders, however, if Capote the literary craftsman, known for the meticulousness of his style, is playing a game by switching the victims’ name with that of actor Tony Lo Bianco, who had appeared recently as a gangster in William Friedkin’s 1971 hit The French Connection – particularly as some JFK assassination researchers have taken an interest in a purported “French Connection” to the conspiracy by way of CIA employment of French or Corsican dope-smuggling mobsters and hitmen [27]. In close succession, Capote renders Leslie Van Houten’s name as “Leslie Van Hooten” [28] – a funny mistake, if it is one, since “Windy Van Hooten’s”, in big-top lore, is the name of a mythical “perfect circus” [29].

Rainer Chlodwig von K.

Rainer is the author of Drugs, Jungles, and Jingoism.

Endnotes

[1] Greene-Whyte, G. “Polanski’s Macbeth”. The

Manson Family Blog (October 25, 2021): https://www.mansonblog.com/2021/10/polanskis-macbeth.html

[2] Ebert, Roger. “Macbeth” Chicago Sun-Times

(1971): https://archive.ph/HI7Ua

[3] Dalzell, Tom. “Barbara Garson’s 7 Years in Berkeley:

From Cuba to MacBird”. Berkeleyside (August 27, 2018): https://archive.ph/UlOHc

[4] Garson, Marvin. “Excerpts from The Staged Sixties”. Kaleidoscope

(May 1970), p. 6.

[5] Alter, Nora M. Vietnam Protest Theatre: The

Television War on Stage. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1996,

p. 199.

[6] Buhler, Stephen M. “Politicizing Macbeth on US Stages:

Garson’s MacBird! and Greenland’s Jungle Rot”, in Moschovakis,

Nick, Ed. Macbeth: New Critical Essays. New York, NY: Routledge, 2008,

p. 268.

[7] Sandford, Christopher. Polanski: A Biography. New

York, NY: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2008, p. 172.

[8] Ibid., p. 174.

[9] Wyllie, Timothy. Love Sex Fear Death: The Inside

Story of the Process Church of the Final Judgment. Port Townsend, WA: Feral

House, 2009, pp. 19.

[10] D’Arcy, David. “Film Reviews – NY Film Festival Closes

– Theater on the Screen”. The Arts Fuse (October 12, 2021): https://archive.ph/kcedL

[11] Stamper, Peta. “Inside the Myth: What Was Kennedy’s

Camelot?” History Hit (November 18, 2021): https://archive.ph/qjqUC

[12] Kuzmarov, Jeremy. “New Evidence Implicates CIA, LAPD, FBI

and Mafia as Plotters in Elaborate ‘Hit’ Plan to Prevent RFK from Ever Reaching

White House”. Covert Action Magazine (September 1, 2021): https://covertactionmagazine.com/2021/09/01/new-evidence-implicates-cia-lapd-fbi-and-mafia-as-plotters-in-elaborate-hit-plan-to-prevent-rfk-from-ever-reaching-white-house/

[13] Norden, Eric. “Playboy Interview: Truman Capote”.

Playboy (March 1968), p. 165.

[14] Stimson, George. “Truman Capote’s Credibility”. The

Manson Family Blog (October 19, 2015): https://www.mansonblog.com/2015/10/truman-capotes-credibility.html

[15] Capote, Truman. Music for Chameleons. New York,

NY: Random House, 1980, pp. 213-215.

[16] Mitgang, Herbert. “Policing America’s Writers”. The

New Yorker (October 5, 1987):

[17] Paikova, Valeria. “What Truman Capote Saw Behind the

Iron Curtain”. Russia Beyond (January 4, 2021): https://archive.ph/k5fPY

[18] Capote, Truman. The Dogs Bark: Public People and

Private Places. New York, NY: Random House, 1973, p. 161.

[19] Ibid., p. 165.

[20] Paikova, Valeria. “What Truman Capote Saw Behind the

Iron Curtain”. Russia Beyond (January 4, 2021): https://archive.ph/k5fPY

[21] Capote, Truman. Music for Chameleons. New York,

NY: Random House, 1980, pp. 215-216.

[22] Ben-Horin, Karen. “Understanding the ‘Party of the

Century’: Q&A with Sarah Rodman”. New York Historical Society

(February 1, 2022): https://archive.ph/tdux8

[23] Norden, Eric. “Playboy Interview: Truman Capote”.

Playboy (March 1968), p. 166.

[24] Capote, Truman. Music for Chameleons. New York,

NY: Random House, 1980, p. 191.

[25] Ibid., p. 216.

[26] Stimson, George. “Truman Capote’s Credibility”. The

Manson Family Blog (October 19, 2015): https://www.mansonblog.com/2015/10/truman-capotes-credibility.html

[27] Valentine, Douglas. The Strength of the Wolf: The

Secret History of America’s War on Drugs. New York: Verso Books, 2004, pp.

226, 314-315.

[28] Capote, Truman. Music for Chameleons. New York,

NY: Random House, 1980, p. 213.

So many great connections. I'd heard of Beausoleil but a quick refresher was rewarding. Great post.

ReplyDeleteThanks! I lost quite a bit of sleep while working on this one.

Delete