2,001 Coincidences

The enigmatic recurrence in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A

Space Odyssey of the form of an ominous black monolith confronts both the

characters and the audience with the possibility of the existence of a much

more advanced intelligence predating man’s own by many millennia. Less

accurately from an architectural standpoint, many writers refer to the object

as an “obelisk” – an interesting word choice in view of its allusion to Middle

Eastern antiquity. Obelisks are associated with solar veneration, sunrises, and

sunsets in ancient Egyptian religion. Indeed, Kubrick famously utilizes the

“Sunrise” from Richard Strauss’s Also Sprach Zarathustra in the sequence

illustrating the painful “Dawn of Man”. Alternatively, “The whole movie is like

watching a sunset,” George Lucas remarks in an interview included in the

documentary Standing on the Shoulders of Kubrick.

In 1968, when MGM released the disturbing science-fiction

masterpiece, the largest share of the company’s stock was held by the Bronfman

family of Zionist billionaires, and Edgar Bronfman would briefly take a role as

MGM’s chairman the following year [1]. “The rise to power of the Bronfman

family has been paralleled by the decline of the United States,” alleges Carol

White in a 1989 issue of Lyndon LaRouche’s Executive Intelligence Review,

which characterizes the family as “part of the ‘invisible government’ which has

never been elected, and yet decides the key questions of foreign and economic

policy for the West.” [2] Bootleggers during the Prohibition years, the

Bronfmans attained a greater respectability through the Seagram brand and within

the world Jewish community through Zionist activism beginning with patriarch

Sam Bronfman’s smuggling of arms to the Haganah [3]. “In the next generation,

the family would move, by marriage, into the very center of the Zionist

Establishment of North America,” a 1992 Executive Intelligence Review

profile summarizes, noting Edgar Bronfman’s marriage to Ann Loeb of the Loeb

banking dynasty [4].

Though also addressing universal themes, 2001 is especially concerned with the trajectory, the achievements, limitations, and eclipse of European man and can be argued to have a particular significance for the American or terminal European man. The same iconic Monument Valley landscape “was made famous by John Ford in movies such as The Searchers (1956) and Stagecoach (1939); by Stanley Kubrick in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968); and by Robert Zemeckis in his films Forrest Gump (1994) and Back to the Future III (1990),” writes Joy Porter. “It was from Monument Valley uranium that scientists made the first three atomic bombs tested in July 1945 at what is now the White Sands Missile Range,” she further observes [5]. The heartbreaking dimension of the “Dawn of Man” segment of 2001 derives from the circumstance that the simultaneously inspiring vision of the hominid’s discovery of technology takes the form of weaponry to be utilized against fellow primates – an arc that culminates in the age of space exploration and nuclear arsenals.

Israel’s own quest for nuclear weaponry, facilitated by the

assassination of John F. Kennedy and the installation in the White House of the

more Israel-friendly administration of Lyndon Johnson, would meet with

disastrous success – aided in part by Zionist asset Zalman Shapiro’s diversion

of hundreds of pounds of uranium from the NUMEC facility in Apollo,

Pennsylvania [6]. The plot was a project of Israel’s intelligence agency LAKAM,

headed by Benjamin Blumberg, and the NUMEC site was visited by Rafi Eitan, who

would later achieve notoriety as the handler of spy Jonathan Pollard. LAKAM was

charged with acquiring the materials necessary for Israel’s nuclear weapons

program, and one of the men recruited to serve that purpose during the 1960s

was future film producer Arnon Milchan [7]. “Milchan’s Malibu home,” note

biographers Meir Doron and Joseph Gelman, “was […] where Senator Robert Kennedy

stayed the night before he was assassinated at the Ambassador Hotel” [8] –

allegedly by a Palestinian terrorist, Sirhan Sirhan [9]. Interestingly, Milchan

would later produce Oliver Stone’s epic JFK (1991), the screenplay for

which attributes the motive for John F. Kennedy’s murder not to Zionism, but

“fascism”.

Among the Hollywood figures Milchan would tap to assist him

in acquiring “arms and other military equipment for Israel in the 1970s” was Three

Days of the Condor (1975) director Sydney Pollack [10], who would later

appear as an actor, playing a rich, sleazy, elite-tier Jew, in Kubrick’s Eyes

Wide Shut (1999), offering a glimpse of an occult world of power. “Pollack,

like Kubrick, was a Jewish director and his physiognomy added what might be

described as a stereotypical Jewish ‘look’,” writes Nathan Abrams, who

characterizes Kubrick’s Jewishness as both striking and incomplete and also

reveals, “In the opinion of Arthur C. Clarke, who co-wrote the screenplay

for 2001, the director’s full and untrimmed facial hair gave him

the ‘aura of a Talmudic scholar’ and the look of a ‘slightly cynical rabbi’

that he retained for the rest of his life” – words encouraging a spiritual

interpretation of their collaboration [11]. The tenebrous object conjured by

Clarke and Kubrick prompts one to wonder if the name of Larry Fink’s asset

monolith BlackRock, founded in 1988, is a reference to 2001 or to some ancient,

ethnically significant archetype.

|

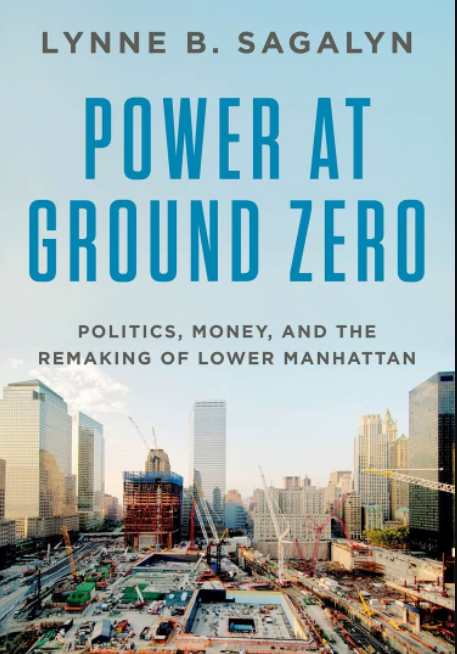

| The cover of Lynne Sagalyn's book shows the proximity of the Millenium Hilton, at far right, to the site of the World Trade Center. |

Beyond the massive impact 2001 had on science-fiction filmmakers like George Lucas and Steven Spielberg, the film seems to have left an architectural imprint on Lower Manhattan in the form of real estate developer and New York Post publisher Peter Kalikow’s monolith-shaped Millenium [sic] Hilton, named in anticipation of the year 2001, designed by Israeli architect Eli Attia, and opened in 1992 [12] – ironic in view of the fact that 1992 is the date 2001 gives for rogue computer Hal 9000’s construction, and also considering that a Hilton accommodation operates on one of the space stations featured in the film. Funnily enough, the Hilton Hotels Corporation would be bought out in 2007 by the Blackstone Group, started in 1985 by Lehman Brothers alumni Peter G. Peterson and Stephen A. Schwartzman. Blackstone is notable for having acquired the mortgage to the curiously fated 7 World Trade Center less than a year before the 9/11 attacks. “We are pleased to be a lender to Larry Silverstein,” states a press release from October of 2000 [13].

|

| Hilton introduced this now-unsettling logo in 1998. |

An ardent Zionist, Peter Kalikow was bestowed the Peace Medal, “the State of Israel’s highest civilian award”, in 1982 [14], and a 1990 issue of New York lumps Kalikow and Edgar Bronfman together as part of the “Barbarian Beach” contingent in the Hamptons hamlet of Montauk, with Steven Spielberg also being known to haunt the vicinity [15]. For backing George Pataki’s New York gubernatorial bid in 1994, Kalikow was rewarded with an appointment as a commissioner of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, in which capacity he served on the subcommittee that transferred the World Trade Center to Benjamin Netanyahu associate Larry Silverstein [16] and his partner, “Holocaust survivor” and Haganah veteran Frank Lowy [17], in 2001 [18]. Silverstein, it so happens, had donated $15,000 to Pataki’s campaign [19]. Kalikow, Spielberg, and Silverstein, incidentally, all purport to have been trustees of the Museum of Jewish Heritage in Battery Park City, a short distance from both the World Trade site and the Millenium Hilton [20]. Kalikow “remains so haunted by the terrorist attack, he’s avoided the area ever since,” his former property the New York Post reported in 2015, adding the irreverent detail that Kalikow’s headquarters at 101 Park Avenue constitutes a “Darth Vader-like tower” [21].

Another member of Spielberg’s generational cohort to be influenced by the Kubrickian vision was Spielberg’s collaborator Robert Zemeckis, who in 1997 directed a movie adaptation of Carl Sagan’s 1985 novel Contact, which bears a thematic relationship to 2001. Kubrick and Clarke had consulted Sagan in preparing 2001, with the latter advising the writers not to overtly depict alien life. “However, the irony is that the cantankerous director disliked Sagan a lot,” writes Mick McStarkey: “Allegedly he told Clarke, ‘Get rid of him. Make any excuse; take him anywhere you like. I don’t want to see him again.’” After toying with the idea of visualizing the alien presence, the auteur nevertheless “would settle on Sagan’s suggestion of insinuating extraterrestrial existence as he saw something in it in the end. This decision would greatly affect the ambiguity of the classic 2001: A Space Odyssey, making it one of the greatest films of all time.” [22] While Zemeckis’s Contact was still in development, “the production crew watched 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) for inspiration,” notes the Internet Movie Database. The Very Large Array astronomical facility utilized in Contact, moreover, “was used 13 years before for a location in the sequel to 2001, 2010: The Year We Make Contact (1984) in which Dr. Floyd is performing maintenance on one of the antennas […]” [22]

More intriguing work by Zemeckis that might not appear at

first glance to have any significance to Kubrick or to 2001 can be found

in the Back to the Future franchise, produced by Spielberg in

collaboration with Neil Canton. This Canton is the brother of Mark Canton [23],

who in the 1970s worked as the executive assistant to Mike Medavoy, the senior

vice president of production at Arthur Krim’s United Artists [24]. Krim, a political

money man and devoted Zionist whose wife had smuggled guns for the Irgun, served

as an unusually pushy adviser on Middle East affairs to the Kennedy and Johnson

administrations during the pivotal years of consolidation of the US-Israel

relationship [25]. Spielberg, a similarly ardent promoter of Israel’s

interests, is Hollywood’s most preeminent advocate of “Holocaust” education and

is also a member of the Mega Group of Zionist billionaires, founded in the

1990s by Jeffrey Epstein handler Les Wexner, World Jewish Congress President

Ronald Lauder, and Edgar Bronfman’s brother Charles [26]. “Ronald Lauder headed

the two commissions under Governor George Pataki that pushed for the

privatization of the World Trade Center: the New York State Commission of

Privatization and the New York State Research Council on Privatization,” notes

researcher Christopher Bollyn: “Lauder was the driving force behind the

effort to privatize the World Trade Center, which resulted in Larry

Silverstein, a fellow Zionist, getting the 99-year lease of the Twin Towers in

July 2001.” [27]

Spielberg, as a young student of film, was profoundly

impacted by Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the

Bomb (1964), which made him “aware of the power of Stanley Kubrick” – an

experience deepened when the young filmmaker saw 2001 at California

State University, Long Beach, “where he waited in line for three hours to catch

the film” and “came out of the film ‘altered’,” writes Debadrita Sur: “He said

that no other film had made him feel the sheer rush of ‘fear’ or the desperate

need to be a part of the ‘great mystery’.” Kubrick, who befriended the Close

Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) director later in life, “had reportedly

told Spielberg, ‘I want to change the form, I want to make a movie that changes

the form.’” [28] Kubrick and Spielberg can certainly be credited

with heightening the sophistication of the motion picture, and Spielberg –

particularly in his collaboration with Zemeckis – has indisputably changed the very

nature of the art form.

Marty McFly, the hero of 1985’s Back to the Future, is introduced to viewers while sleeping, just as Dr. Floyd is introduced in 2001 – unconscious and unprepared for the threat that the future holds. Marty lives in Hill Valley, a smallish California town that very much finds the hominid’s bone on the downward whirl of the toss, administered by a black mayor and with a dirty bookstore and a porno theater operating in the town square. The marquee of Hill Valley’s Essex theater portentously indicates that a movie titled Orgy American Style is playing. Vice and usury prevail, with a loan office open but a nearby small proprietor’s window sporting an “out of business” notice.

Another notable landmark is the town’s “Clock Tower” – a

designation that draws attention to itself owing to the fact that “tower” is

rather an unintuitive term to describe the building. Once struck by lightning,

the tower is now in danger of being destroyed. “Save the Clock Tower!” warns a

woman handing out flyers. The glasses worn by this woman and one of her fellow

“Save the Clock Tower” activists visible in the background may superficially

indicate nerdiness, but can also indicate a differing level of perception – a

theme famously central to John Carpenter’s They Live (1988). In a later

scene, Doc Brown appears in strange lenses after returning from the future

bearing disturbing foreknowledge. Marty, introduced as a sleeper, lacks the activists’

sense of alarm, being preoccupied instead with pop culture and becoming a rock

star. 2001’s Dr. Floyd, similarly, has fallen asleep while watching

in-flight television. The imperiled Tower, a theme reprised from Zemeckis’s

I Wanna Hold Your Hand (1978), invites reference to the lightning-struck Tower

card in the masonic Rider-Waite tarot, associated with cataclysmic upheaval – a

connection encouraged by the detail that Marty’s adversary Biff Tannen lives on

Mason Street. The character was named after Universal Studios executive Ned

Tanen, whom writers Bob Gale and Robert Zemeckis “had met […] during

a script meeting for I Wanna Hold Your Hand where Tanen had

reacted in aggressive fashion to their writing, accusing them of attempting to

produce an anti-Semitic film.” [29] (Marty’s brother, it may be worth noting,

is named Dave – like the astronaut who confronts the malevolence of HAL 9000 in

2001 – and Dave threatens to be erased from existence if Marty is

unsuccessful in his time-travel adventure. George McFly, father of Marty and

Dave, meanwhile, is, like Arthur C. Clarke, an author of science-fiction

stories.)

Another sinister element of Back to the Future is the danger posed by Arab terrorists, in this case Libyans seeking plutonium for nuclear weapons. The terrorists shoot Doc Brown in the parking lot of Hill Valley’s Twin Pines Mall, and part of Marty’s mission entails the prevention of this misfortune. Interestingly, the name of the property later changes to Lone Pine Mall after events in the past have been altered as a result of Brown’s “temporal experiment”. More than one observer has noted Back to the Future’s multiple examples of latent occurrences of the numerals 9-1-1. Brown conducts his “temporal experiment” at 1:16 am – which, rotated upside-down, makes 9-1-1. A second shot of Brown’s watch indicates that the time is 1:19 am – a backwards 9-1-1. Finally, the film’s climactic sequence leaves a pair of flaming tire marks on a nighttime street, which in combination with the looping neon Western Auto arrow to the left, constitutes another 9-1-1, a disturbing resonance in view of the film’s theme of a warning about a future catastrophe and the Rider-Waite parallel of the sequence’s lightning-struck Tower. Introducing a metafilmic dimension, moreover, is the presence of a Fox Photo kiosk in the parking lot of the Twin Pines Mall – alluding both to star Michael J. Fox and the idea that film takes time to develop – its full significance unknowable in the moment. Confirming Back to the Future’s metafilmic content, Christopher Lloyd at one point breaks the fourth wall, pointing directly at the viewer and promising, “Next Saturday night [i.e., the night of the lighting strike], we’re sending you back to the future!” In perhaps another metafilmic touch, Lloyd’s character expresses an interest in traveling twenty-five years into the future – which would place him in the year 2010, the setting of Clarke’s sequel to 2001 – although he later opts instead for 2015.

Confirming the franchise itself as a “temporal experiment”, Zemeckis and Spielberg released the bleakly visionary Back to the Future Part II on November 22, 1989 – the anniversary of the JFK assassination. This sequel develops air travel as a feature of the franchise’s depiction of 2015, with opening credits appearing over a flight through the clouds. As in the first film, the theme of a Middle Eastern threat is introduced early on, with a diner’s video menu displaying a Headroom-style rendering of Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini. Not long thereafter, Biff’s thuggish descendant Griff goes flying through the façade of what was once the Clock Tower, now repurposed as the Hill Valley Courthouse Mall. Apprehended by authorities, Griff protests: “I was framed!” In a different scene, adding another subtle hint of a Middle Eastern significance, a Luxor taxi appears, possibly in allusion to Luxor’s Valley of the Kings as a sister site to Back to the Future’s ruined Hill Valley with its dying civilization. The driver’s door is marked “B-25” – also a type of bomber aircraft – and a warning on the roof of the cab reads, “watch your head” – cheeky advice in view of the fact that Doc Brown’s flying DeLorean is nearly struck by a plane flying overhead elsewhere in Back to the Future Part II.

The putatively false attribution of the responsibility for an attack on the Tower is all the more interesting in light of the appearance of the Twin Towers later in the film. Marty’s aged father George is shown entering his home as he hovers in an upside-down position. As Israeli esotericist Joe Alexander has pointed out, George’s inverted perspective presents the key to understanding the mise-en-scene of what follows [30]. In the family’s living room, the malfunctioning television – described as a broken window – is tuned to the Scenery Channel as it broadcasts a static shot of two trees. The trees are then replaced onscreen by a view of the Twin Towers, which with a tape-roll effect appear to move upward. From George’s upside-down perspective, however, the impression is that the Twin Towers are falling. A miniature replica of the Statue of Liberty in proximity to the broken window-television demonstrates that the room is a simulation of New York City on September 11, with a fire extinguisher sitting nearby on the floor – as if in anticipation of a blaze – and Marty in the first movie has warned his parents that the house may be set on fire. The towers-trees equivalence is a call-back to the transformation of the sign in the first film from the Twin Pines Mall to the Lone Pine Mall, a shockingly prescient detail in consideration of the eventual replacement of the Twin Towers with One World Trade. Then, too, there is this seemingly nonsensical piece of rudeness from Biff: “Why don’t you make like a tree and get outta here?”

“You’ll find out in thirty years,” viewers of the 1985 film are told. As if to put the finishing touches on the decades-spanning geopolitical “temporal experiment” in postmodern stagecraft called 9/11, Zemeckis in 2015 – exactly thirty years later, during the very year he had depicted in Back to the Future Part II – would release The Walk, which stars Joseph Gordon-Levitt as Philippe Petit, the high-wire artist who staged a stunt at the World Trade Center in 1974. The film depicts Petit training for his feat by walking a line suspended between two trees – confirming the Towers-trees correspondence Zemeckis and Spielberg had employed in Back to the Future and Back to the Future Part II. One of The Walk’s executive producers was corporate attorney Ben Waisbren, formerly a managing director and head of investment banking restructuring at Citigroup subsidiary Salomon Brothers [31], whose offices at 7 World Trade were destroyed along with thousands of records required for ongoing Internal Revenue Service, Securities and Exchange Commission, and Equal Employment Opportunity Commission investigations when the Salomon Brothers building collapsed in a strange symmetrical free-fall on September 11, 2001. “This is a disaster for these cases,” Max Berger of Bernstein Litowitz Berger and Grossmann was quoted as saying in a National Law Journal article published six days later, “because so much of their work is paper-intensive.” [32]

The Spielberg-Zemeckis Back to the Future franchise

shares with Kubrick’s 2001 the theme of wonderment at European man’s inventiveness

as well as a mingling of pessimism, sympathy, and contempt as the bone falls

back to the earth. 2001: A Space Odyssey, on the one hand, presents the

viewer with an optimistic vision of boundless technological progress but

couples with it a prophecy of the hostile commandeering of technocracy by a

mysterious other. In the 1960s, when Kubrick and Clarke designed their film,

audiences might be persuaded to see in their future a dazzling consummation of

European achievement in elegant solar crosses rotating through the depths of outer

space to Austrian waltzes. Only a creeping sense of unarticulated anxiety might

have undermined the certainty of that graceful trajectory. By the 1980s, when Orgy

American Style erupted into the town square, demography loomed, and

neoliberalism was hitting its stride, even the most optimistic picture of America’s

future was tarnished by commercial tackiness and dysgenics and darkened by deliberately

vicious occult and subliminal undercurrents. As to the identity of that black alien

monolith eternally present, do we really need to ask?

Rainer Chlodwig von K.

Rainer is the author of Drugs, Jungles, and Jingoism.

Endnotes

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edgar_Bronfman_Sr.

[2] White, Carol. “The Bronfmans: Part I”. Executive

Intelligence Review vol. 16, no. 34 (August 25, 1989), p. 50.

[3] Faith, Nicholas. The Bronfmans: The Rise and Fall of

the House of Seagram. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press, 2007, p. 125.

[4] “The Bronfmans: Rags to Rackets to Riches to

Respectability”. Executive Intelligence Review vol. 19, no. 27 (July 1,

1992), p. 20.

[5] Porter, Joy. Land and Spirit in Native America.

Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2012, p. 104.

[6] https://www.israellobby.org/numec/

[7] Doron, Meir; and Joseph Gelman. Confidential: The

Life of Secret Agent Turned Hollywood Tycoon Arnon Milchan. Lynbrook, NY:

Gefen Books, 2011, p. 48.

[8] Ibid., p. 245.

[9] K., Rainer Chlodwig von. “JFK, RFK, John Frankenheimer,

and the Mystery of Sirhan Sirhan”. Esoteric Brezhnevism (August 2,

2020): https://rainercvk.blogspot.com/2020/08/jfk-rfk-john-frankenheimer-and-mystery.html

[10] Olson, Marie-Louise. “‘I’m Proud of What I Did’:

Hollywood Producer Reveals His Double Life as an Arms Dealer and Israeli Spy –

And Says the Late Sydney Pollack Participated Too”. Daily Mail (November

22, 2013): https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2511965/Arnon-Milchan-reveals-details-double-life-arms-dealer-Israeli-spy.html

[11] Abrams, Nathan. “How Jewish Was Stanley Kubrick?” Zocalo

(September 19, 2018): https://www.zocalopublicsquare.org/2018/09/19/jewish-stanley-kubrick/ideas/essay/

[12] https://nyc-architecture.com/LM/LM064.htm

[14] https://web.archive.org/web/20170602010401/http://mjhnyc.org/pressroom/documents/Heritage08.pdf/

[15] Gross, Michael. “Star Hamptons”. New York (July

2-9, 1990), pp. 32-34.

[16] Leibovich-Dar, Sara. “Up in Smoke”. Haaretz

(November 21, 2001): https://archive.ph/39q9K

[18] Sagalyn, Lynne B. Power at Ground Zero: Politics,

Money, and the Remaking of Lower Manhattan. New York, NY: Oxford University

Press, 2016, p. 49.

[19] Leibovich-Dar, Sara. “Up in Smoke”. Haaretz

(November 21, 2001): https://archive.ph/39q9K

[21] Cuozzo, Steve. “9/11 Still Haunts Real Estate Czar,

Ex-MTA Chair Kalikow”. New York Post (April 13, 2015): https://nypost.com/2015/04/13/911-still-haunts-real-estate-czar-ex-mta-chair-kalikow/

[22] McStarkey, Mick. “How Carl Sagan Influenced Stanley

Kubrick Masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey”. Far Out (May 12,

2021): https://faroutmagazine.co.uk/how-carl-sagan-influenced-stanley-kubrick-2001-a-space-odyssey/

[23] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_Canton

[24] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mike_Medavoy

[25] Weiss, Philip. “The Not-So-Secret Life of Mathilde

Krim”. Mondoweiss (January 26, 2018): https://mondoweiss.net/2018/01/secret-life-mathilde/

[26] Levine, Barry. The Spider: Inside the Criminal Web

of Jeffrey Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell. New York, NY: Crown, 2020, p.

119.

[27] Bollyn, Christopher. “9/11: The Lauder/Rothschild

Connection”. Christopher Bollyn (May 26, 2019): https://bollynbooks.com/9-11-the-lauder-rothschild-connection/

[28] Sur, Debadrita. “Steven Spielberg Explains the Impact

and Influence of Stanley Kubrick”. Far Out (May 22, 2021): https://faroutmagazine.co.uk/steven-spielberg-explains-the-influence-of-stanley-kubrick/

[29] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ned_Tanen

[30] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AFqOJO1Gn34

[32] Fisk, Margaret Cronin. “SEC and EEOC: Attack Delays

Investigations”. National Law Journal (September 17, 2001): https://archive.ph/m7MR3

Comments

Post a Comment