The US-Sponsored Assault on the Portuguese of Angola

In 1961, at the outset of the decades-long

and convoluted series of struggles over Angola’s political future, the first

group to seriously challenge Portuguese colonial authority was Holden Roberto’s

Union of Peoples of Angola (UPA), a recipient of aid from the United States. “The

war started with dollars,” Portugal’s Captain Ricardo Alcada told South African

journalist Al J. Venter a few years later. “The Americans thought that by

backing Holden Roberto they would chase the Portuguese out of Angola within

months,” Alcada explained [1]. “They had no option,” he continued: “They had to

counter the communist influence in Congo-Brazza across the river so they chose

the likeliest candidate for ‘Mr. Overnight Pro-America’ among the sanguinary

rabble they found wandering about downtown Kinshasa.” [2] “The Americans

realize their mistake now, but they are still allowing money into the Congo

from a number of organizations,” he further enumerated: “Numerous church and

social groups in the United States, Britain and other European and Asian

countries are passing on money to the terrorists – over and above what they

receive from the Iron Curtain states.” [3]

Roberto’s UPA fighters were among

the worst savages in Africa and would slaughter thousands when they invaded Portuguese

Angola in 1961. Catching the Portuguese off-guard, Venter writes, “the

terrorists had managed to kill 1,700 White Portuguese men, women and children

and between 20,000 and 30,000 Africans – the people they had come to ‘liberate’.”

[4] Venter continues his account of how Americans’ tax dollars were spent in

undermining one of the few remaining European colonial presences in Africa:

Meanwhile

Roberto’s men were laying waste to farms and buildings wherever they found

them, he [Brigadier Martins Sorrés] continued. Everyone in their path was

killed – Black, White, old or young; even babies were not spared. They were

often cut open and stuck on to stakes along the road. […]

The brigadier

maintained that the explanation for the early success of the terrorists was

simple. Many of the Freedom Army soldiers believed they were under the

spell of their witch-doctors and that the bullets of the enemy would be turned

to water. They thought they were invincible and that nothing could stop them. “It

is difficult to stop a man who thinks like that,” he said.

“When they attacked

they came on screaming and firing their weapons. Others followed behind

wielding spears, pangas and machetes. They were fearless and equally ruthless.”

The cry as the insurgents attacked was always “Mata! Upa! Mata! Upa!” (Kill!

Upa! Kill! Upa!). […]

It was more than

a month before the Portuguese found their feet again. [5]

Captain Alcada furnished Venter with an anecdote indicative of the horrifying sights that might await a young man conscripted to serve in the war:

It was late April

1961, he told us. He was a young alfares then, in charge of his own

platoon. “We came down this stretch in the early hours one morning towards

Nambuangongo […]

“We were in three

jeeps. I travelled in the first one, as we officers usually do.

“As we came out

of the darkness to this spot I felt uneasy. I still do not know why. I asked

the driver to slow down. We came around that corner,” he said pointing.

“In the road ahead

of us was the head of a woman on a stake.”

“It was

obviously a symbolic warning of sorts put there by the terrorists. They had

been bold in the early days. It was a mysterious, ominous warning and one that

I will never forget. It is imprinted on my mind as if it were yesterday. I can

still see the dark cavities where her eyes had been,” he said.

The head was

partly decomposed. He could see she had been Portuguese. Her hair was long and

black – unlike negroid hair. She had apparently been the wife of the owner of

that farm, Ricardo nodded toward the ruins.

“We never found

her body. God only knows what medicine they used it for.”

That was the

night, Ricardo continued, that started him off in this war – good and proper.

“I was completely

shaken up, even though it was an ordinary incident. There have been many others

since – some far worse. But that one had a special significance for me.

“My immediate

reaction was one of revolt. I wanted to kill everything black that I could lay

my hands on. At the same moment I realized I had three black soldiers under my

command in the patrol with me. The effort to control my instincts was not easy.

I had to satisfy this primitive lust for blood. […]

“I swore there

and then that I would become a name to be feared among the terrorists.” [6]

|

| MPLA leader Agostinho Neto with UPA's Holden Roberto |

The government of Israel was sufficiently impressed with the UPA’s performance that it would provide aid to Roberto’s revolutionary movement throughout the decade. Though eventually overshadowed by Agostinho Neto’s more disciplined and communist-aligned People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), the UPA’s achievement in shaking Portuguese authority and worsening racial tensions in Angola was considerable. “The terrorists used the simple maxim of Mao Tse Tung,” a Portuguese commandant informed Venter: “to take a country, it is first necessary to create chaos and revolution by every means possible,” adding: “And what better catalyst for revolution than friction between the races”? “It was a young lieutenant who made the most erudite observation of all,” Venter writes: “It seems that there is someone else applying those same principles on a far more subtle plane in the United States – and obtaining better results.” [7]

Rainer Chlodwig von K.

Rainer is the author of Drugs, Jungles, and Jingoism.

Endnotes

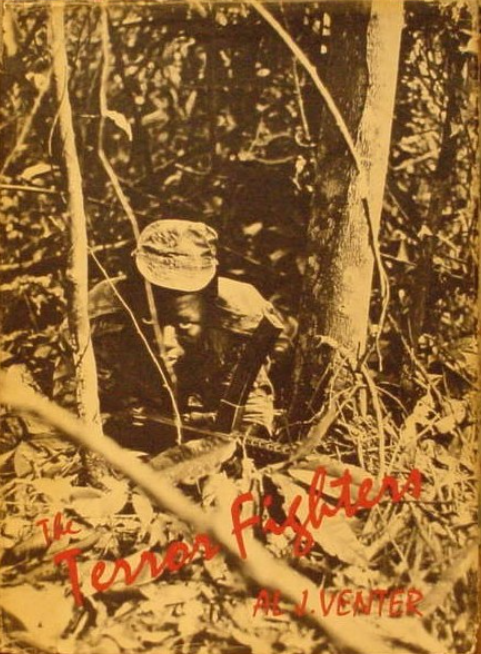

[1] Venter, Al J. The Terror

Fighters: A Profile of Guerrilla Warfare in Southern Africa. Cape Town:

Purnell, 1969, p. 61.

[2] Ibid., p. 63.

[3] Ibid., p. 61.

[4] Ibid., p. 13.

[5] Ibid., pp. 13-14.

[6] Ibid., pp. 66-67.

[7] Ibid., p. 112.

Comments

Post a Comment