Machismo, Misogyny, and Hypocrisy in Posadism

|

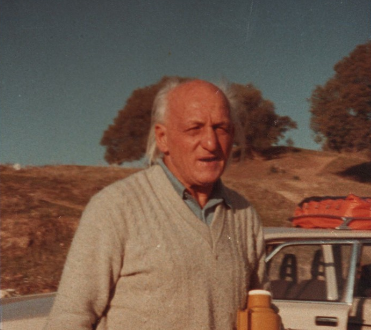

| J. Posadas (1912-1981) |

The Posadist Fourth International, founded by the Argentinian

eccentric J. Posadas, became notorious for its leader’s enthusiasm for nuclear

war and willingness to incorporate ufology and pseudoscience into his Marxist

philosophy. By the 1960s, Posadism was exhibiting characteristics of a cult,

with the cruel and charismatic but not particularly intelligent Posadas revered

as a figure of mystic insights. “Any signs of individualism, in behavior or

opinion, were mercilessly critiqued,” writes A.M. Gittlitz in his recently

published book I Want to Believe: Posadism, UFOs, and Apocalypse Communism.

“Even one comrade telling Posadas that he was ‘the best of all us’ drew a

rebuke since he was not an individual, but the prime mover and sum total of

parts.” [1] Posadas’s ego played the major role in the movement’s trajectory,

however; and what may surprise the reader of Gittlitz’s book more than the talk

of extraterrestrials or communication with dolphins is the extent to which

Posadas evinced what today is characterized as “toxic masculinity” – a trait that

may be inseparable from the movement’s Latin American roots.

Posadas, who had played soccer competitively as a

young man, used to mandate cadre participation in matches after their

congresses: “Posadas took great pride in showing off his skills in these

demonstrations of the importance of teamwork, sometimes elbowing or tripping

opponents to show the need to be tough.” [2] Giving expression to this machismo,

one of Posadas’s representatives at an international congress of Trotskyists

chastised “insane” political nemesis Ernest Mandel for “being a pussy who

doesn’t believe in thermonuclear war!” [3] Further:

Homosexuality, considered

capitalist degeneracy, was entirely banned. Anyone found to actually be gay,

such as Peruvian section veteran Ismael Frias, was immediately expelled.

Rivals, especially Ernest Mandel, were repeatedly referred to as “faggots”.

Closeted members of the movement learned to suppress their feelings or at least

keep them a secret. [4]

Sexually conservative – at least publicly – Posadas

denounced the looseness and frivolity he perceived in his Cuban counterparts’

activities: “The congresses which they (the Cubans) hold are genuinely

shameful. For example, many youth are attracted to them by women and dances,”

he complained. “The meetings are simply an excuse.” [5] Those who criticized

him he dismissed as “sexual degenerates”. [6]

Posadas believed “advances in technology, social

organization, and human reason would destroy basic bodily urges” and that

people in the future would “only desire sex for procreative purposes.” [7]

“Militants were constantly criticized for showing signs of immorality,”

Gittlitz notes [8], and he sometimes demanded that spouses separate in order to

better concentrate on party tasks. Having moved his headquarters to Italy,

Posadas invited militant Guillermo Almeyra to join him in a gesture that “was

both an acknowledgment of his importance to the party, and a punishment – his

wife Ana Teresa was ordered to stay in Buenos Aires so his libidinal energies

would be focused solely on the party.” [9]

|

| Is the homophobic Posadas spinning in his grave? |

Gittlitz relates a British Trotskyist’s memories of

Posadism’s austere morality:

David Douglass remembered

him [i.e. Posadas’s disciple Adolfo Gilly] teaching at a cadre school in

England. After the long day of lectures, he was disgusted to see Douglass and

his comrades opening beers, criticizing them for “lumpen drinking”. Later that

night, as the cadre got ready to sleep, Gilly became even more agitated.

“[W]hat was going on?” Douglass remembered Gilly asking, “Male comrades and

female comrades, together? In the same room together? … This isn’t a hippy

festival, we can’t have mixed sexes together, all together, this is

degenerate.” [10]

The party’s irascible leader at times displayed

hateful attitudes toward women, exhibiting a “cruel coldness” toward Italian member

Piero Leone’s wife, for example. [11] “In Uruguay, a militant couple left the

party after Posadas accused the wife of committing adultery and ordered them to

release a self-criticism statement,” Gittlitz recounts. [12] Suspicions of

infidelity would come to occupy an increasingly prominent place among Posadas’s

preoccupations during the 1970s.

As events would reveal, Posadas fell far short of his

own ascetic sexual ideal:

One night an Argentine

comrade staying at Posadas’s villa awoke to find his girlfriend was not in bed.

His search of the house led to the master bedroom, where he turned on the light

to find her performing fellatio on Posadas. The young comrade’s shouts awoke the

rest of the inner circle, who gathered in the kitchen to argue about what had

occurred.

It was clear Posadas had

broken his own moral code, but in the weeks that followed he deflected his

crime against his inner circle by accusing them of the same promiscuity. It

began with his driver, a man from Florence who shuttled blindfolded militants

between Rome and the Villa. One day the driver was banned without explanation.

Then Posadas began to make vague criticisms against [his wife] Sierra. Leone

gathered Posadas was accusing her of infidelity, but it was unclear if he was

being literal or metaphorical. He remembered her responding “with an almost

autistic attitude: silence, very little eating, no admission of guilt, but no

defense against the accusations.”

Telling his militants

that he refused to be a cuckold, he sent Sierra to live in the German section.

His “farewell” speech for her was just as vague as the accusations and

disturbingly as cold as all his rare references to her in internal documents. […]

As he pushed out his

wife, Posadas developed an interest in a young Argentine militant named Ines.

He accused her husband, Marcos, of indiscipline and sent him away, leaving Ines

at the Villa to do everything Sierra had once done, Leone realized: “wiping his

back after football matches, preparing the mate, and so on.”

Soon he came to make the

same vague criticisms against Ines that he had made against Sierra, and, in the

final weeks of 1974, a full year after these obsessive speeches on sexual

impropriety, began to expel his inner circle one by one. During the process he

finally made his accusations clear. He believed Sierra and Ines had been “fucking

more or less all the men [who had been expelled],” Leone wrote. Posadas knew

this was happening because he could hear an unmistakable coital creaking of

furniture from his bedroom. [13]

“Posadas announced his partnership with Ines in a

lengthy speech” after she “admitted her faults (the many acts of adultery), and

thanks to that had been forgiven,” Leone remembered. “The necessity of a compañera

is not a sexual problem,” Posadas defended himself. “I don’t need a compañera

for this. I can get by.” Instead, he said he needed her “to have a method to

elevate the affective life” and “develop my capacity for feelings of

conscience, my capacity for organizing.” [14]

Ines bore Posadas a daughter, Homerita, for whom he

eventually hired a tutor, a young woman named Rene, in 1980. “It was around this

time Posadas openly abandoned his personal code of sexual morality,” Gittlitz

reveals:

Sex was now, for him at

least, about more than just having children. “Yes, the sexual act is

procreative, together with the sexual act bringing ideas. […] And they are

suggested in the moment of doing it.” By the end of the year Rene became his

new romantic obsession, and his old sexual paranoiac fantasies returned. On 29

October, he held a meeting to denounce two men in the party who he claimed were

sleeping with Rene, a scene so dramatic he says she threatened suicide.

More accusations came in

the first days of 1981, when he awoke early to sounds he believed to be her having

sex with someone in the kitchen.

Posadas declared that Rene was “evil”, though he later

reunited with her. [15] His steady mental decline and cycle of hypocritical sexual

adventurism and paranoia ended when he died that year; and, given the extent to

which today’s online neo-Posadism overlaps with dreams of “fully automated luxury

gay space communism”, the visionary’s macho misogynist program of gender

regimentation would seem to have died along with him.

Rainer Chlodwig von K.

Rainer is the author of Drugs, Jungles, and Jingoism.

Endnotes

[1] Gittlitz, A.M. I Want to Believe: Posadism,

UFOs, and Apocalypse Communism. London: Pluto Press, 2020, p. 84.

[2] Ibid., p. 88.

[3] Ibid., p. 82.

[4] Ibid., pp. 84-85.

[5] Ibid., pp. 93-94.

[6] Ibid., p. 152.

[7] Ibid., p. 151.

[8] Ibid., p. 152.

[9] Ibid., p. 127.

[10] Ibid. p. 138.

[11] Ibid., p. 124.

[12] Ibid., p. 106.

[13] Ibid., pp. 142-143.

[14] Ibid., p. 145.

[15] Ibid., p. 153.

Comments

Post a Comment