70s Punk: An Ur-Alt-Right?

Many years ago – sufficiently long ago that it was

back when watching a VHS tape just happened to be the way a guy experienced

video content if he hadn’t bought a DVD player yet, rather than it being an

exercise in hipster consumerist nostalgia – I remember borrowing a cassette of a

1978 documentary, Blitzkrieg Bop, which profiles the “punk cult” that

emerged around the Ramones and the CBGB scene in New York during the

mid-to-late 70s. I’ve always remembered the corny tone of the narration and the

hilarity of Village Voice journalist Robert Christgau proclaiming punk

rock “very dangerous. It could lead to fascism. All of that is really true. No,

you laugh,” he addresses those

who would scoff. “All of that is really true.

Yes, there is – there is an extraordinarily dangerous energy that these people

are trying to unleash. How much of it there is in this country remains to be

seen.” He pronounces punk “productive”, however, to the extent that it

redirects this dangerous energy. Christgau, it seemed to me at the time, was

taking the naughty allusions of songs like “Blitzkrieg Bop” and “Today Your

Love, Tomorrow the World” rather too seriously. I was reminded of Christgau’s

remarks recently – and prompted to wonder if my previous dismissal of his

thesis had been justified – when I watched Penelope Spheeris’s classic 1981

documentary The Decline of Western Civilization, which takes as its

subject the late-70s-early-80s punk scene in Los Angeles.

One of the first things that will strike the viewer –

particularly today – is the casual racism of several of those featured in the

film either as interviewees, performers, or attendees at concerts. The opening

credits montage of raucous punk crowds even freezes on a man wearing an arm

band that simply says “HATE”. What emerges from Spheeris’s interviews with

performers and fans from the scene is that it was largely energized by the same

factors – alienation, racial tension, and sexual frustration – that motivate

today’s Alt-Right. Boastfully violence-prone young interviewee “Michael”, for

example, confesses, “I don’t have girlfriends,” but says this is because “girls

are terrible.” Stronger misogyny emerges in the interview with Georg

Ruthenberg, a musician of mixed black, Native American, and Jewish background

who played guitar with the Germs and would go on to work with Nirvana and the

Foo Fighters under the name Pat Smear. “I probably hit lots of girls in the

face,” he tells Spheeris in footage not included in the final cut of the film.

“I don’t like girls very much. […] They were real snotty. They were callin’ me

bad things, they were callin’ me dirty words.”1 In addition, The

Decline of Western Civilization shows Fear frontman Lee Ving taunting his

audience of “fags” in a diatribe that today would be deemed “homophobic”.

|

| A Fear fan displays his arm for the camera in Penelope Spheeris’s The Decline of Western Civilization. |

Another young punk Spheeris interrogates is “Eugene”,

a skinhead loner who explains that “short hair is just the clean-cut American

look, man.” Asked about the source of

his anger, he says “it just comes from, like, livin’ in the city and just seein’

everything, seein’ all the ugly old people and just the fuckin’ buses and just

the dirt […] so when I go there I just, sometimes I can get out some

aggression, maybe, by beatin’ up some asshole, you know.” In another clip, he

reveals that “sometimes some niggers will come up to me and, like, you know […]

they’ll start chasin’ me, like, you know, most times around in L.A., yeah, I

get chased a lot.” One interviewee, “Kenny”, is a bizarre Asian wearing a

swastika T-shirt. “But it doesn’t really mean […] I’m gonna go kill a Jew,” he

says. “You know, I’m not gonna do that. Maybe a hippie, though,” he adds with a

smile.

Swastikas make multiple appearances in the film,

including on the torso of Germs lead slurrer Darby Crash, whose kitchen counter

is also shown decorated with a skull wearing a Nazi helmet. Crash’s friend

Michelle Baer tells Spheeris the story of finding a dead Mexican painter in the

backyard of her parents’ home and posing for pictures with the corpse. “It was

really funny, actually, and the paramedics came and they were joking with us,

and the coroner came,” she says. Crash inserts that “instead of ‘John Doe’ they

put down ‘José Doe’ because it was a wetback.” When Spheeris inquires whether

she felt bad that a human being had died, Baer replies, “No. Not at all.

Because I hate painters. I hate it when they paint our house.” Asked about the

dead man’s family, she says, “Yeah, his brother and his mom or something came

and they couldn’t speak English. They were speaking, like, broken English ‘cause

they were Mexican, and – and we’re just sitting there laughing and stuff and

they’re like, all, you know, when somebody dies in your family.”

|

| Darby Crash of the Germs gets down and deplorable in The Decline of Western Civilization. |

Los Angeles was ground zero for the rapid demographic

transformation of the United States during the late twentieth century – a

situation that prompted one of the city’s most notable punk acts, Black Flag,

to create their song “White Minority”. Half of the immigrants who arrived in

the US during the 1970s and 1980s were bound for California2, so

that it quickly became “the Ellis Island of the 1980s” as The New York Times

profiled the metamorphosing metropolis in 1981:

In a tide of immigration

that is reshaping the social, economic and political life of the nation's most

populous state, California has become the port of entry for tens of thousands

of refugees from economic and political troubles abroad. […]

According to

demographers, not since the turn of the century, when millions of immigrants

from southern and eastern Europe flocked to America and settled in New York and

other cities along the East Coast, have so many alien immigrants from so many

countries gravitated to a single region of the country. […]

Because much of the

immigration is illegal, no one knows how many newcomers are arriving here from

abroad. Based on data from the Immigration and Naturalization Service, however,

the legal migration to California from abroad last year is believed to have

ranged from 150,000 to 200,000, including about 50,000 Southeast Asians. The

state’s total population growth was about 450,000. […]

From 1970 to 1980,

according to the bureau's figures, the proportion of California residents who

are “Anglos”, that is, those whose ethnic roots are predominately in Western

Europe, declined to 76 percent from 89 percent. The proportion of virtually

every other ethnic category increased substantially. […]

The immigration has had a

variety of effects on life in California. In places like Beverly Hills and

Marin County, north of San Francisco, money brought by immigrants from Korea

and Hong Kong has been cited as one reason for California's hyperinflated real

estate market over the last six years.

In other areas, those

that attract the far larger proportion of immigrants who come without much

money, officials say that tensions are rising between different ethnic groups

because of competition for jobs and housing. […]

Some officials expect the

tensions between people at the lowest rung of the economic ladder to increase

as the size of the minority population grows.

“It’s like a keg of

dynamite with a one-inch fuse,” said Fred Koch, a deputy superintendent of

schools in Los Angeles County, who sees tensions mounting, especially among

blacks, Hispanic Americans and Indochinese refugees.3

It makes sense that metropolitan areas like Los

Angeles or Detroit, which experienced localized demographic apocalypses, would

witness the emergence of something akin to the Alt-Right roughly thirty or

forty years ahead of the rest of the country. Proto-punk band Iggy and the

Stooges, who were from Michigan, but would make a memorable live impact in

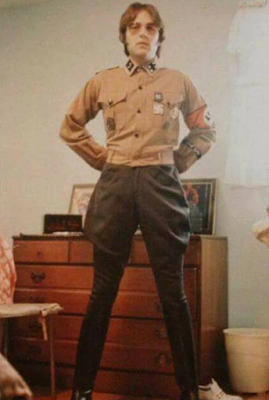

California, were no strangers to racial provocation. Guitarist Ron Asheton was

a well-known Nazi aficionado, and leader Iggy Pop dedicates the song “Rich

Bitch” to the “Hebrew ladies in the audience” in the 1974 live recording

released as Metallic K.O.. Asheton, in an interview contained in the

book We Got the Neutron Bomb: The Untold Story of L.A. Punk, relates the

following anecdote from the mid-70s:

One day Iggy Said, “Hey,

you got any of those Nazi uniforms of yours with you in L.A.?” And I said,

“Yeah, I got a couple of things.” And he said, “Well, we’re doing this show at

Rodney’s and I want you to dress up in the Nazi uniform and whip me. We’ll get

you some beers and stuff.” So I took a couple of my buddies down there and

that’s what I did. I just showed up in my brown shirt. Iggy had a bass player

and drummer and they were just playing this weird rhythmic music and Iggy was

trying to incite people. Iggy got up in this black dude’s face and was really

trying to provoke him, and I thought, “God, if I was that guy, I would fucking

deck him.” Then he got out a rusty pocketknife and started cutting himself up.4

|

| The Stooges’ Ron Asheton in character |

Jon Savage, in his book England’s Dreaming,

highlights the racial themes that were cropping up in the music and aesthetics

of punk bands across America, from New York to Detroit to a post-apocalyptic

urban Cleveland that was “totally deserted” and where “people fled when the sun

went down”5:

The Cleveland groups used

the same building blocks as New York or London, but their development in

isolation resulted in a Bohemianism that was proud to fail. “The most

nihilistic were the Electric Eels,” says [Cleveland native and Psychotronic

magazine founder Michael] Weldon. “John Morton was the leader: he and Dave E.,

the singer, wrote the songs, which had funny, clever lyrics. There was a lot of

violence attached to that group. John liked to call it Art Terrorism. Brian

McMahon, the guitarist, and John would go out to working-class bars where

people worked in steel mills, and dance with each other. That caused serious

fights.

“In 1974, they were

wearing safety pins and ripped-up shirts, T-shirts with insulting things on

them, White Power logos and swastikas: it was offensive and they meant to be

offensive. They meant to distract people, but I don’t think they were

exceptionally racist: they were being obnoxious and outrageous. Live they were

often too out of control. I don’t think they seriously thought anything was going

to happen except they were going to go out there and get arrested.” […]

Pere Ubu were the first

new Cleveland group to make it out of the city: in the winter of 1975 they

travelled to New York to play Max’s [Kansas City] and CBGBs. In March 1976,

they released “Final Solution”, a stripping down of Blue Cheer’s “Summertime

Blues” into a “dumb teen angst song” so nihilistic that the group, concerned by

the Nazi images in the new culture, refused to play it live. […]

“Lose his senses,” sang

Television in “Little Johnny Jewel”. This exploration of the subconscious began

to disinter the strange gods of the time. Lurking under nihilism’s cloak was a

slight but persistent trace of the right-wing backlash that was brewing in the

West from the mid-1970s on. “We don’t believe in love or any of that shit,”

says one of the editors of Punk in its first issue, as they state in the

Ramones interview: “Dee Dee likes comic books, anything with swastikas in it,

especially Enemy Ace.”6

|

| Handbill for a 1974 Electric Eels show. |

“As premier teenage music, above all punk aims to

shock the established order and empower powerless youth,” writes Donna Gaines

in Why the Ramones Matter:

What better way to rile

‘em up than celebrating the Nazis, Satan, Charles Manson, gangsters, serial

killers, outlaws. Stick it! According to Mickey Leigh, Johnny especially

embraced these figures. For kids who want to slam it to the social order, these

are the go-to guys.

“Today Your Love,

Tomorrow the World”, the last track on Ramones, is a first-person

narrative of a small-town German kid who is tired of being pushed around,

treated like shit. The original lyrics were changed from a proud Nazi’s

first-person narrative to that of a disoriented shock trooper still hell-bent

on defending the Fatherland. According to Monte Melnick, Seymour Stein, the

founder and president of Sire Records (the Ramones’ first label), was horrified

by the first incarnation of the song. “You can’t do that,” he said. “You can’t

sing about Nazis! I’m Jewish and so are all the people at the record company.”

Monte, Joey [Ramone, born Jeffrey Hyman], and Tommy [Ramone, born Thomas

Erdelyi] were Jewish too. Reworking the lyrics, Tommy transformed them from a

glorification to a parody of Nazis. As Johnny explains in retrospect: “We never

thought anything of the original line. We were being naïve, though. If we had

been bigger, there would have been a bigger deal made of it by the press.”

Ironically, for Johnny, the lack of recognition for the band likely shielded

them from scandal.7

“Final solutions of various types were invoked to

hasten the death of the old culture, but Nazi images persisted,” Savage

continues:

The Ramones were

initially packaged by an artist called Arturo Vega, who lived in a loft next

door to CBGBs: “Everybody hung out there,” says [journalist] Legs McNeil:

“Arturo was a gay Mexican and a minimalist artist who made dayglo swastikas.”

The Ramones’ early material was spattered with references to militarism and

acronymic organisations like the CIA or the SLA, with more explicit references

in “Blitzkrieg Bop” and “Today Your Love, Tomorrow the World”.

“What they want, I don’t

know,” sang the Ramones about their generation: the formal severity of

their music lent such slogans an absorbing ambiguity. “I would have arguments

about this stuff,” says Mary Harron. “Arturo had some really nasty ideas, but

Joey Ramone was a nice guy, he was no savage right-winger. The Ramones were

problematic. It was hard to work out what their politics were. It had this

difficult edge, but the most important thing was needling the older generation.

Hating hippies was a big thing.”

“The [also largely Jewish

band] Dictators came from Co-op City in Detroit, the Ramones came from Forest

Hills, we came from Cheshire [Connecticut],” says McNeil. “We all had the same

reference points: White Castle hamburgers, muzak, malls. And we were all white:

there were no black people involved with this. In the sixties hippies always

wanted to be black. We were going: “Fuck the Blues; fuck the black experience.”

We had nothing in common with black people at that time: we’d had ten years of

being politically correct and we were going to have fun, like kids are supposed

to do.

“It was funny: you’d see

guys going out to a Punk club, passing black people going into a disco, and

they’d be looking at each other, not with disgust, but ‘Isn’t it weird that

they want to go there.’ There were definite right-wing overtones, but we didn’t

feel like, ‘Let’s go out and start a youth movement about fascism’ or anything.

I don’t think anyone wanted to read too much depth into it: it was more

emotional. When the imagery was used, it was more like ‘Look at these guys,

isn’t it stupid?’”8

Raymond Patton, in his book Punk Crisis: The Global

Punk Rock Revolution, situates the advent of punk in Britain within a

context of national and racial angst:

The economic crisis was

compounded by a crisis in British identity. Great Britain was an empire by

definition, but it had been hemorrhaging its colonies since World War II. For

some white English citizens accustomed to holding a clear place at the top of a

global hierarchy, the whole world order seemed to be inverted. Instead of

enterprising Britons conquering the world, they fretted over the influx of

“colonials” from around the world – especially West Indians and South Asians –

who had returned [sic] to the metropol in search of new opportunities. Some

argued that English culture was threatened by these new residents, as Enoch

Powell notoriously envisioned in a 1968 speech predicting an inevitable

conflict between Britain’s ethnicities, flowing in “rivers of blood.” Powell

was no longer active in politics by the mid-1970s, but amid growing doubts

about national greatness, concern about immigrants posing a threat to law and

order (including a mugging scare in 1972 that was tinged with racist imagery),

and finally, the recession, radical right-wing nationalist groups like the

National Front and the British Movement rose in popularity polls. Finally, the

existential crisis facing the United Kingdom directed special attention toward

English youth, the future standard-bearers of the nation.

In the context of

ideological crisis, distress over declining greatness, and concern over youth,

punk had the potential to arouse more than casual concern, even among elites

who normally wouldn’t deign to address popular culture. In this context, the

scandal over the Sex Pistols’ release of “God Save the Queen” and performance

on the Thames during the queen’s Silver Jubilee brought punk to the floors of

Parliament in the summer of 1977. By taking on the monarchy, the Pistols

transcended the realm of political debate, striking at a symbol at the heart of

British pride, culture, and imperial potency.9

“The monarchy was a powerful symbol for many in the

working class – and they were willing to use the weapons of the workers’

movement to defend its image,” Patton further explains, differentiating between

the politically nebulous and iconoclastic Pistols and the patriotic,

working-class Teddy boys:

Teddy boys, the

working-class subculture of the previous generation, still revered God, queen,

and country and were willing to take up arms to defend those values from punks.

Punk-Ted violence was sometimes inflated and sensationalized by the press, but

punks also saw its serious side: John Lydon [aka Johnny Rotten] was injured by

Teds shouting, “We love our queen” as they attacked him with a knife.

As punk evoked panic,

scorn, and rage across political and class lines, punks reciprocated,

dispensing their vitriol without consideration of conventional boundaries. Even

the Clash, which established a reputation for sympathizing with the Left,

distanced itself from the Labour Party. In a January 1978 interview on the BBC2

youth program Something Else, [Joe] Strummer explained to MP Joan Lestor,

chairman of the Labour Party, “Most young people feel remote from the mechanics

of government, they don’t feel a part of it. It’s just so boring, it doesn’t

interest anyone. All the parties look the same and it looks a big mess.” Punk

band The Jam went even further to separate itself from a comfortable slot on

the Left, claiming it would vote conservative in the next election. For the

most part, though, mainstream politicians of all stripes had difficulty

adapting to punk. This left an opening for creative thinkers on the margins of

the political spectrum who showed greater flexibility in adapting punk to their

interests.10

Patton mocks a 1977 National Review article by

Edward Meadows that “characterized punk as the music of right-wing

working-class rage against the failed welfare state”, but concedes that Meadows

“was on target in one respect: punk did not seem to fit with the mainstream

left. Its anti-hippy ethos, lack of respect for working-class culture,

disregard for doctrinaire second-wave feminism, and willingness to use symbols

from all over the political spectrum separated it from the political left of

the previous decade,” he continues:

What Meadows missed was

that punk didn’t fit any better with the resurgent far right. It lacked the

reverence for nation and race that formed the core of radical right-wing

politics; the pomp and grandeur of the British Empire was part of the mythology

that punk deflated.

The far right made other

overtures as well – such as when the Young National Front newspaper, Bulldog,

added a Rock Against Communism supplement. But when Bulldog tried to

claim Johnny Rotten in 1978, Rotten made it clear that the feeling wasn’t

mutual – he told the Rock Against Racism fanzine Temporary Hoarding that

he “despised” the National Front on grounds of its inhumanity. Even more

forthright in rejecting the far right was the Clash, which explicitly declared

itself antifascist and antiracist. The members of the Clash might not be Labour

supporters, but neither were they willing to be co-opted for the National

Front. Within a few months, a core of punk groups including the Clash launched

a massive counteroffensive – a litmus test for punk’s potential for cooperation

with the far left.11

(Notwithstanding their high-profile participation in

the Rock Against Racism concert of April 1978, however, it is interesting to

note that black crime features prominently in “Safe European Home”, the opening

track of the Clash’s second album, Give ‘Em Enough Rope. The song memorializes

a November 1977 trip made by Joe Strummer and Mick Jones to Jamaica, “the place

where every white face is an invitation to robbery.” The songwriters “don’t

glamorize or idealize the trip but rather express that they felt endangered in

Jamaica, even ripe for the picking as white guys hanging around the harbor

buying weed,” writes Martin Popoff in The Clash: All the Albums, All the

Songs. “It didn’t help that Jamaica was essentially undergoing a civil war

at the time.”12)

However much Rotten might have “despised” the National

Front, the Sex Pistols’ multiple references to Nazism outraged many – which, of

course, was the point. Michael Croland, in Oy Oy Oy Gevalt: Jews and Punk,

observes that “two of the group’s four singles referred to fascism or the

Holocaust,” elaborating:

The vague Belsen mention

in “Holidays in the Sun” was controversial, but the song “Belsen Was a Gas”

went despicably too far. The Sex Pistols began performing “Belsen Was a Gas” in

late 1977, and it did not appear on the group’s only proper full-length record.

The song title referred to a pun suggesting that concentration camps’ gas

chambers were a good time. (The reference was not historically accurate, as

there were no gas chambers at Belsen.) The song’s narrator sang about Jews’

graves and “fun” in consecutive lines.13

The jokes about gas chambers and gays and the

disrespectful attitudes displayed toward women in vintage manifestations of

punk culture can hardly fail to evoke the Alt-Right for viewers in the Trump

era. The difference today is that the suicidal-homicidal race malaise is no

longer restricted to urban anxieties, but permeates an impendingly non-white

America, with Black Flag’s “White Minority” no longer sounding like merely another

instance of grim punk rock shock value, but rather an imminent prophecy for all

of us in the western world. Punk, to the limited extent that it was

identitarian in outlook or expression, was ultimately an escapist and

self-destructive avenue for racial angst instead of an outwardly directed

social or political movement. What seems fun and exciting in The Decline of

Western Civilization, however, is increasingly shadowed by a more

depressing, more dangerous sense of urgency today.

Rainer Chlodwig von K.

Rainer is the author of the books Drugs, Jungles,and Jingoism and Protocols of the Elders of Zanuck: Psychological

Warfare and Filth at the Movies.

Endnotes

1. “Light

Bulb Kids” (special feature). Spheeris, Penelope, Dir. The Decline of

Western Civilization Collection [DVD] (1981-1998). Los Angeles, CA: Shout!

Factory, 2015.

2. Pastor,

Manuel. “California Used to Be as Anti-Immigrant as Trump. Don’t Repeat Our

Mistakes”. Los Angeles Times (March 15, 2018): https://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-oe-pastor-california-immigration-history-20180315-story.html

3. Lindsey,

Robert. “California Becomes Melting Pot of 1980’s”. The New York Times

(August 23, 1981): https://www.nytimes.com/1981/08/23/us/california-becomes-melting-pot-of-1980-s.html

4. Spitz,

Marc; and Brendan Mullen. We Got the Neutron Bomb: The Untold Story of L.A.

Punk. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press, 2001, p. 27.

5. Savage,

Jon. England’s Dreaming: Anarchy, Sex Pistols, Punk Rock, and Beyond.

New York, NY: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2001, p. 137.

6. Ibid.,

pp. 134-137.

7. Gaines,

Donna. Why the Ramones Matter. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press,

2018, pp. 90-91.

8. Savage,

Jon. England’s Dreaming: Anarchy, Sex Pistols, Punk Rock, and Beyond.

New York, NY: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2001, pp. 137-138.

9. Patton,

Raymond A. Punk Crisis: The Global Punk Rock Revolution. New York, NY:

Oxford University Press, 2018, p. 80.

10. Ibid.,

p. 83.

11. Ibid.,

pp. 83-84.

12. Popoff,

Martin. The Clash: All the Albums, All the Songs. Minneapolis, MN:

Quarto, 2018, p. 52.

13. Croland,

Michael. Oy Oy Oy Gevalt: Jews and Punk. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger,

2016, p. 33.

Comments

Post a Comment